Can regional clusters be engineered?

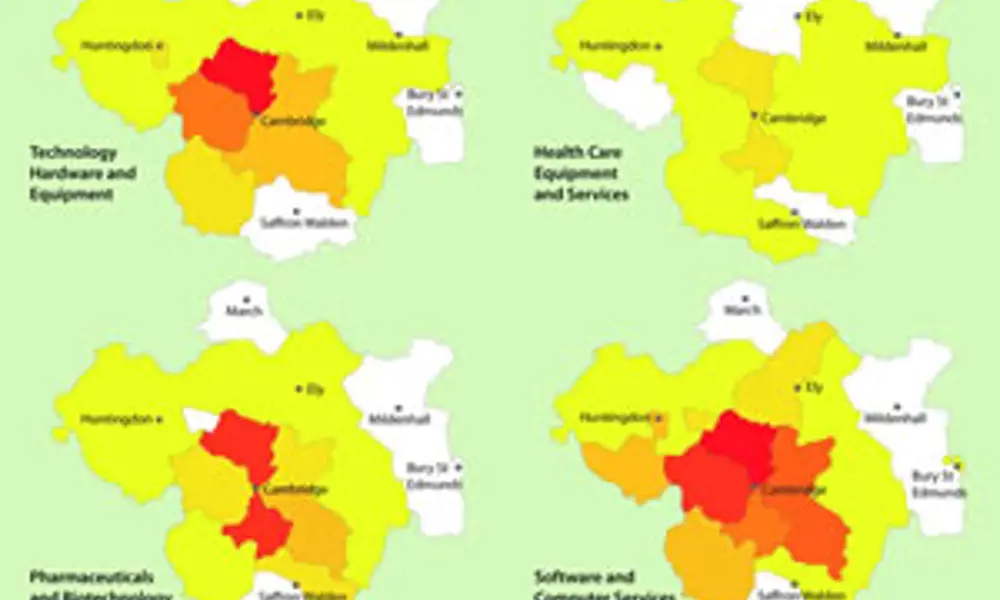

The Cambridge Cluster is a dynamic environment, with new companies incorporating and more mature companies relocating, merging or going out of business. The area contained within the Cambridge Cluster is approximately 80 km across, accounting for an area of approximately 2100 km2 Diagrams reproduced from The Supercluster Question – The Cambridge Cluster Report 2006 © Library House

A healthy set of start-up companies in high-technology industries is widely seen as important for developed countries. It is believed that such companies drive innovation, generate growth and generally enable a country to make good use of key knowledge workers. New companies tend to develop in groups or ‘clusters’. Professor William Webb FREng has studied the phenomena in the UK and considers whether these clusters can be manufactured.

There is no precise definition of exactly what constitutes a cluster, although most would agree that it means companies working in the same or related fields of science and technology and grouped in the same geographical area.

There are many clusters throughout the UK. Oxfordshire, for example, is the home of motorsports, including most of the Formula1 industry. The Midlands is historically a centre for manufacturing.

Perhaps the best-known of the UK’s hi- tech clusters is in Cambridge. Sometimes known as ‘Silicon Fen’, Cambridge is a key area for start-ups in telecommunications and biotechnology. Something like 25% of all the high-technology start-ups in the UK originate within the Cambridge Cluster and around 7% of the venture capital for all of Europe is directed there.

Cambridge appears so successful at generating high-technology start-ups that many other areas of the UK have sought to replicate the effect, often through regional initiatives. The InfoLab21, for example, seeks to promote a vibrant start-up community in Lancaster by forming strong links between academia and industry. To date, however, initiatives aimed at starting new clusters have had limited success.

The Cambridge Cluster

Entities such as clusters are ideal research territory for management institutions, and much has been written about the Cambridge Cluster. The intention here is to provide an overview on the key issues.

The seeds that led to the cluster were sown in the early 1970s. In 1970, Trinity College opened the Cambridge Science Park. At that time there were just two science parks in the UK; the second, set up a year later, was at Heriot-Watt University near Edinburgh, later dubbed ‘Silicon Glen’.

The Cambridge Science Park encouraged a slow and steady growth in the number of new companies and consultancies in the area. It was not until 1985 though that the phenomenon began to be recognised and the cluster label first appeared. Growth in Cambridge then accelerated into the 1990s and peaked around 2000, maintaining an approximate steady state after that. It is not clear if the slow-down is an effect of the global problems with telecommunications and whether growth will subsequently resume. Certainly there is still a lot of appetite within Cambridge to move back into strong growth.

Researchers who have looked at the Cambridge Cluster, still argue over how and why it came about. Most agree that a number of factors have played a part in creating what has come to be known as the ‘Cambridge phenomenon’.

Random attraction?

The first key factor seems to be that the Cambridge cluster emerged through a bottom-up rather than top-down process. It was not due to central planning by, for example, a regional administration, but through the uncoordinated actions of a number of key individuals.

The links with the University of Cambridge and its colleges were also an important factor. This was initially through the provision of a research park by a couple of colleges and then through the willingness, sometimes passive rather than active, of the university to allow members of staff to develop their ideas commercially. It is also postulated that the reputation of Cambridge both attracted the highest quality individuals as students and entrepreneurs who wished to benefit from a link to a prestigious body. Finally, the Cambridge brand is very powerful around the world, providing credibility to companies linked to the university.

Some also suggest that the establishment of key consultancies was critical. An early example, Cambridge Consultants, had the dual advantage of both attracting highly skilled individuals to the area and creating an environment where other companies – both consultancies and start-ups – were readily spun off. Indeed, the role of consultancies could be more important than that of the university.

Individuals make a difference

A few key individuals played a major role in the history of the Cambridge phenomenon. For example, Hermann Hauser was involved in Acorn Computers. At first acting as an ‘angel investor’, using his own funds and expertise to nurture new businesses, Hauser subsequently formed Amadeus Capital. This fund has provided venture capital to many major Cambridge companies and has been involved in a number of initiatives to further the role of Cambridge (read more about Hermann Hauser in Ingenia 33).

A further factor in the growth of the Cambridge Cluster has been the importance of the many networks of individuals that exist in the area. For example, the Cambridge Network brings together key individuals across multiple disciplines and maintains links with alumni, often in other countries, linking the cluster to other important international clusters. The networking has now developed to such an extent that there is even one promoting innovation and entrepreneurial thinking among the university’s undergraduates.

To summarise, some of the recurring elements in the emergence of successful clusters are: the presence of a few key individuals who establish successful companies; help in the forming of local networks; the provision of angel funding; and the presence of the right environment in terms of academic and consulting opportunities.

Home preferences

Can areas that lack these attributes still develop clusters? The evidence and intuition strongly suggests that most entrepreneurs start up companies where they happen to be located. On top of all the risks and stress of a start-up, few want, or consider it necessary, to relocate. Hence, any attempts to form a cluster, rather than to leave one to emerge organically, must either attract into the region people who will go on to form new companies, or encourage those already living locally to become entrepreneurs.

Existing clusters are good at doing both, tending to attract focused, skilled staff into the region to work for established companies. They also encourage individuals to start up their own companies both because the infrastructure to do so is in place and because individuals have positive exposure to those who have successfully started companies already. The risks for start-ups in the area are reduced because even if they fail, they are likely to be able to find other opportunities without needing to relocate.

All this makes it clear that it is relatively hard to start a cluster, but once formed successfully a cluster should become self-sustaining. It also suggests that it might be progressively harder to form clusters. Once a few clusters are established, they will attract entrepreneurs away from other areas and into a new area – just as it is progressively harder for competitors to enter an established market unless they can differentiate themselves in some way.

The problems faced by anyone wanting to create new clusters also raises the intriguing question as to whether a country is best served by having a few large clusters or multiple smaller ones. However, while regional development agencies consider their geographical areas in isolation – with many trying to clone existing biotechnology clusters, for example – answering this question is not likely to change current policy, at a regional level at least.

How to seed a cluster

Experience suggests that successful clusters start themselves. There is little evidence that it is possible to proactively start a successful cluster, especially given that it gets increasingly hard to succeed after the first successful cluster is established. Indeed, the evidence from those who have tried to start clusters is just that – it is very difficult.

Success has been patchy. Having said that, the Cambridge Cluster took around 15 years to become noticeable and a further ten to become a major entity. Few regional initiatives continue for such a long time. To some degree then, it may be too early to judge, or it may be that clusters have been adjudicated failures and the funding stopped too soon.

A key ingredient for any new cluster is the need for a few key individuals with successful track records as entrepreneurs. This is because these individuals start their own companies – often going on to start a series of high-tech companies – and act as role models. These serial entrepreneurs provide encouragement and their successes persuade others to follow in their footsteps. (See examples of Professor Sir Michael Brady and Professor Peter Denyer on the opposite page.)

These individuals also bring funding with them, either directly through their own angel funding or indirectly through their contacts with venture capitalists. They also bring critical experience. Research shows that start-ups are much more likely to succeed where they have strong involvement from successful entrepreneurs.

Academic connections

There are other factors that may be helpful in the birth of a cluster. A link to a university provides an increased flow of ideas, adds to the pool of individuals who may become entrepreneurs and is a key mechanism for developing a science park. However, the evidence suggests that the university link will provide only a small percentage of ideas and individuals. In any case, with most universities in the UK boasting a science park or some other form of incubator – there are now more than 100 science parks in the UK – it is hard for any one university to stand out in the way that Cambridge and Heriot-Watt did in the 1970s.

Good infrastructure is appealing, but of less interest to high-tech companies than manufacturers, especially if it comes, as it does in some locations, at an elevated price tag. Financial support may also help a little, particularly for marginal cases.

Finally, the ‘product champions’ for any new cluster help in forming local networks that can share knowledge. They can form critical links between individuals and can provide something of a safety net and lobby for change where needed. Equally important, they can introduce sources of finance into the networks that they help to create.

A word of caution

Although the Cambridge Cluster is widely admired, it generates relatively little wealth and employment for the region. Even the most successful companies, such as ARM and CSR, both with huge stock-market valuation for their businesses of creating chips mostly for telecommunications applications, employ relatively few people in the region.

The successes in Cambridge have generated substantial wealth for their founders but have had little overall effect on, say, employment or the average salary in a region. Why this is the case is also the subject of much discussion and is not conclusive. For example, a different funding model that did not require an exit strategy for investors within a few years might aid longer term growth. However, regional development agencies should be aware that even if they beat the odds and form a cluster it is unlikely to solve all of the problems in their region.

Does this mean that all the current efforts to form clusters are in vain? Not necessarily. They may work if the region can import a few key individuals or if such individuals can be ‘home grown’ and the venture can be given sufficient time. Finally, in a changing world, what has worked in the past may not prove to be applicable in the future.

Biography – Professor William Webb FREng

Professor William Webb joined Ofcom as Head of Research and Development and Senior Technologist in 2003. He previously worked for a range of communications consultancies in the UK and spent three years providing strategic management across Motorola’s entire communications portfolio. William has published ten books, is a Visiting Professor at Surrey University, was elected a Fellow of The Royal Academy of Engineering in 2005 and is a Fellow of both the IET and the IEEE.

Keep up-to-date with Ingenia for free

SubscribeOther content from Ingenia

Quick read

- Environment & sustainability

- Opinion

A young engineer’s perspective on the good, the bad and the ugly of COP27

- Environment & sustainability

- Issue 95

How do we pay for net zero technologies?

Quick read

- Transport

- Mechanical

- How I got here

Electrifying trains and STEMAZING outreach

- Civil & structural

- Environment & sustainability

- Issue 95