Should we trust connected devices?

The growing market for connected home devices brings with it potential benefits for individuals, society and the economy. Personalised services are emerging that could improve individuals’ quality of life, such as those that support assisted living, or help improve energy efficiency or physical security. Smart meters stand to bring benefits both to the energy industry and consumers, as well as the environment. Other benefits for consumers from home devices might include greater convenience, decision-making support and remote control of home services when the individual is not physically present.

The furore around Facebook’s mismanagement of personal data brings into the spotlight the commercial and other interests involved in the collection, sharing and processing of personal data, and the associated threats to privacy. As the number of Internet of Things (IoT) devices in people’s homes grows, I believe there is potential for aspects of people’s lives to be observed to a greater degree. For example, certain devices can collect potentially sensitive audio and video information from microphones or cameras. It is also then possible to infer information about individuals based on when and how a device is being used.

As the number of Internet of Things (IoT) devices in people’s homes grows, I believe there is potential for aspects of people’s lives to be observed to a greater degree

Consumer applications of IoT bring both benefits and risks. Do those risks justify the decision to connect home devices to the internet? What actions should individuals take to mitigate them? As consumers, should we trust these devices? As the reach of the IoT grows, it is vital that home devices are both trusted and dependable for their benefits to be realised.

A recent report by the Royal Academy of Engineering and a consortium of universities – the PETRAS Cybersecurity of the Internet of Things Research Hub – Internet of Things: realising the potential of a trusted smart world, raises policy, design and research issues for IoT.

As for social media, many business models for home devices rely on people’s willingness to share their personal data. Users may be unaware of, or indifferent to, the default configuration of devices. Consumer devices such as Amazon Echo – a home audio speaker system with a voice-activated virtual assistant called ‘Alexa’ that can control several smart devices using itself as a home automation system – are set with camera and voice always on. Smart TVs now include voice activation, and are listening to and sharing data. People also trade privacy for services; for example, illegal add-ons to Kodi boxes enable data sharing in return for free access to subscription TV services. Media reports highlight the potential for surveillance with warnings on smart toys and smart toasters. News stories about Alexa’s ‘creepy laugh’, when several of the systems mistakenly operated without users instructing them to, are likely to increase people’s perceptions of ‘being watched’.

As for social media, many business models for home devices rely on people’s willingness to share their personal data. Users may be unaware of, or indifferent to, the default configuration of devices

A further report by the Academy, Cyber safety and resilience: strengthening the digital systems that support the modern economy, highlights that ‘cyber safety’ – the ability of connected devices and systems to protect individuals or property from harm during a cyberattack or accidental event – is a key challenge. The ability for an individual to operate a smart device remotely has safety implications if they cannot directly observe what that device is doing; for example, if they are operating an electric heater or oven remotely. A hacker’s ability to control a device remotely could also have ramifications, for example if the hacker is able to disable a security alarm or unlock the front door.

Many consumer products are coming to market with little or no attention to the security of the devices, the data they gather, use and transmit, and the privacy and safety risks if security is compromised. For example, a hacker may be able to communicate with a child via a smart toy, or to observe when a home is occupied. Away from the home, the impact of a security breach is not limited to the IoT device and the information it holds alone, but affects the security and resilience of connected infrastructure globally. This was exemplified by the large-scale attack in 2016 launched using the ‘Mirai botnet’ – a computer virus that targets online consumer devices – that resulted in several high-profile websites, including Twitter, Netflix and Airbnb, being made inaccessible.

A vital role for manufacturers is to ensure that software updates are available throughout the lifetime of a product and are rapidly distributed to consumers when security vulnerabilities are discovered

The government’s report on the security of consumer IoT, Secure by Design, recognises that, while clear information for consumers is important, it should not be left to them to securely configure their devices: manufacturers must build strong security into their products by design. A vital role for manufacturers is to ensure that software updates are available throughout the lifetime of a product and are rapidly distributed to consumers when security vulnerabilities are discovered. More broadly, I believe that engineers have a responsibility to consider safety and security in all their work, including IoT. It remains to be seen to what extent manufacturers will adopt the voluntary code of practice put forward by government. In the meantime, advice for consumers on how to protect themselves is emerging. The Information Commissioner’s Office has published tips on buying smart toys that include turning off the ability to remotely view footage from web cameras and changing default passwords on devices and routers.

There are both legal and ethical issues around how personal data is used and shared by the companies that collect it. The question of how the EU General Data Protection Regulation, which came into force at the end of May 2018, will work in the world of IoT is still unclear. Practical approaches to privacy and trust require significant technical effort, but are beginning to emerge. Personal data stores allow consumers to control how they share data with organisations, with potential benefits to both. Well-designed human–device interfaces help to mitigate risks. Technologies that allow consumers to protect their privacy, such as allowing them to decide the information they are willing to share with third parties and what third parties can use that information for, are under development but have not yet reached the market.

The advice from consumer groups is clear: ‘If you don’t trust it, don’t buy it’. Suppliers of home devices urgently need to change their practices, but until they do so, it seems that consumers will need to continue to take an active role in protecting their privacy and security if they do decide to connect their home devices.

***

A copy of the Academy reports mentioned can be found at:

Internet of Things: realising the potential of a trusted smart world

Cyber safety and resilience: strengthening the digital systems that support the modern economy

This article has been adapted from "Should we trust connected devices?", which originally appeared in the print edition of Ingenia 75 (June 2018).

Contributors

Paul Taylor FREng is Partner and UK Head of Cyber at KPMG LLP. He has led the delivery of some of the most demanding national security programmes in the UK. He is a member of several government technical advisory committees.

Keep up-to-date with Ingenia for free

SubscribeRelated content

Software & computer science

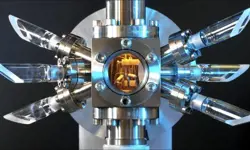

Compact atomic clocks

Over the last five decades, the passage of time has been defined by room-sized atomic clocks that are now stable to one second in 100 million years. Experts from the Time and Frequency Group and the past president of the Institute of Physics describe a new generation of miniature atomic clocks that promise the next revolution in timekeeping.

The rise and rise of GPUs

The technology used to bring 3D video games to the personal computer and to the mobile phone is to take on more computing duties. How have UK companies such as ARM and ImaginationTechnologies contributed to the movement?

EU clarifies the European parameters of data protection

The European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation, due for adoption this year, is intended to harmonise data protection laws across the EU. What are the engineering implications and legal ramifications of the new regulatory regime?

Evolving the internet

He may have given the world the technology that speeded up the internet, but in his next move, Professor Nick McKeown FREng plans to replace those networks he helped create.

Other content from Ingenia

Quick read

- Environment & sustainability

- Opinion

A young engineer’s perspective on the good, the bad and the ugly of COP27

- Environment & sustainability

- Issue 95

How do we pay for net zero technologies?

Quick read

- Transport

- Mechanical

- How I got here

Electrifying trains and STEMAZING outreach

- Civil & structural

- Environment & sustainability

- Issue 95