Sir David McMurtry FREng FRS - Turning patents into profits

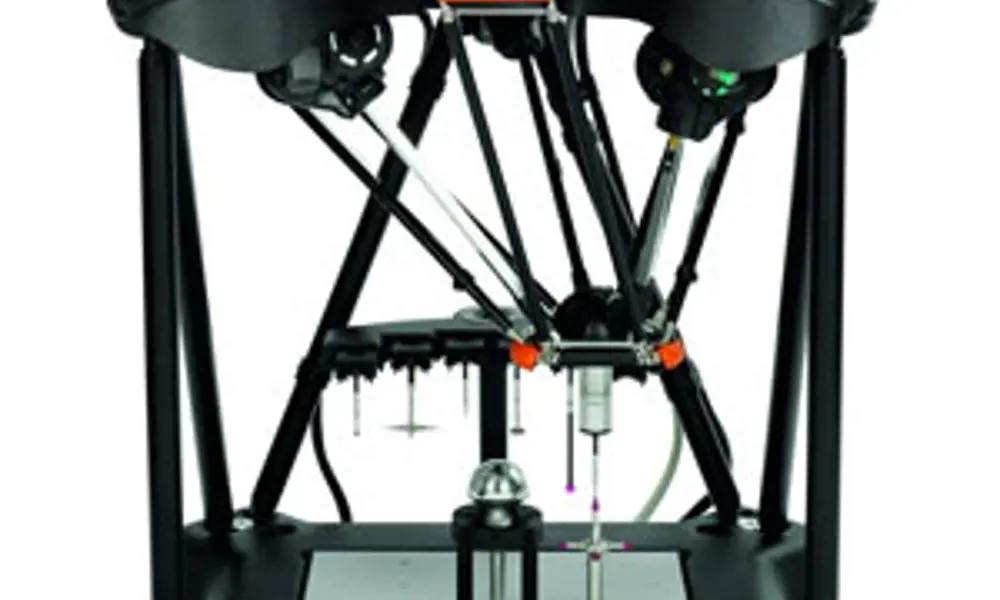

Renishaw’s ‘Equator’ is a high-speed system for inspection of high-volume manufactured parts in a machine shop, helping to maintain product quality

When Rolls-Royce had measurement problems with the engines for the Concorde supersonic airliner, Sir David McMurtry came up with a solution that not only helped the aircraft to take off but also launched a business that has transformed modern manufacturing. He talked to Michael Kenward about the importance of metrology in quality control and how Renishaw’s systems have become a global standard for companies that want to demonstrate their credibility as efficient manufacturers.

It was model aeroplanes that first triggered Sir David McMurtry’s interest in engineering. He was a keen aero modeller from the age of eight and put a lot of time and effort into modifying the aircraft’s small diesel engine to give him an edge when team-racing his plane. When it came to getting a job, Sir David thought that it would be in the aircraft industry. When he had finished his schooling, it was with the ambition to become an aero engine designer.

Early ambition

Sir David, born and brought up in Dublin, had to overcome a series of obstacles in his quest. After Rolls-Royce had turned him down, he applied for a job at Bristol Aero Engines. His interview, he says, consisted mostly of dismantling his model-aircraft engine to demonstrate his modifications. The company was impressed, but it did not understand the value of his Irish exam certificates, so offered him a job as an apprentice machinist and fitter, with the promise that if he did well he could move on to a student apprenticeship. He says: “I did four years before I was allowed to be a full-time student. Then I did another four years studying, obtaining an HND at the Bristol College of Science and Technology, and by the time I finished that, I was really old!”

On graduating, Rolls-Royce, which by then had taken over Bristol Aero Engines, offered Sir David a job in its design office where he found himself alongside “a large Oxbridge contingency” of younger graduate recruits. However, he soon discovered that his period as an apprentice, making things, served him in good stead. He was, he says: “far more practical than those younger recruits. By the age of 30 I was deputy chief designer and over those other guys.”

By this time, Sir David was realising his early ambition to design aero engines. He was head of the design team of the ‘hot end’ of the RBB-199, the turbofan engine for the Tornado multi-role combat aircraft. He was also deputy chief designer for the RB.401 and ran the ultra-quiet engine programme, laying the foundations for later generations of turbofan engines.

Birth of an idea

His career-changing moment came when Rolls-Royce called Sir David in as a troubleshooter on the far-from-quiet engines that were to power Concorde. Rolls-Royce could not figure out how to make accurate measurements of the small fuel pipes in the engine. The old manual approach – push in a probe and measure its position – was just not precise enough. The McMurtry solution was a three-pronged ‘remote sensing’ electrical probe that triggered a signal when the probe hit the pipe’s surface.

Many an engineer would have seen that invention as a job well done before moving on to the next challenge, but Sir David saw something bigger. He realised that, by devising the 3D remote-sensing touch-trigger probe, he had come up with something that could change the face of metrology, the underlying science of measuring what is going on in manufacturing. He thought the idea had potential and took it to his bosses at Rolls-Royce. The company may have needed better metrology to make jet engines, but it wasn’t in the business of making probes and measurement systems. So Sir David decided, with his bosses’ approval and backing, to go it alone. Well, not quite alone: John Deer, a colleague at Rolls-Royce, also saw the potential for this by now patented invention.

At the time, the beginning of the 1970s, Sir David had no plans to venture out into the business world on his own. “I saw it as a business potential but I still saw my career as being with Rolls-Royce.” So he made the first probes himself while Deer set about turning them into a business. “John was prepared to get the bits made, assembled and sold while I stayed on at Rolls-Royce,” says Sir David.

Renishaw started operations as a company in 1973, but it wasn’t until 1979 that Sir David finally left Rolls-Royce and moved full time to Renishaw. He tried to break away earlier, but Rolls-Royce asked him to stay on for three days a week to complete the work on the ultra-quiet engine. A model of the engine, a leaving present from the company, now sits in Renishaw’s headquarters.

Quality control

The company’s business is all about helping people to make things. “We help people to do quality control more precisely and more effectively. This is all part of modern engineering,” says Sir David. “Reliability is everything. These are basically the tools that allow you to verify this before items go out the door.” As such, it has contributed to rising quality and reliability in manufacturing. As Sir David puts it: “There are no ‘Friday cars’ these days. You don’t get big pistons and small cylinders like we used to get in the good old days!”

Renishaw may be about to celebrate its 40th birthday, but the company’s name is little known outside manufacturing circles. “We are completely hidden because we are business-to-business,” Sir David explains. “The average person will not have heard of Renishaw. But if I walk into a manufacturing plant in Japan we are known. I don’t think that there is any engineering facility over there that hasn’t got our bits and pieces.” And manufacturers in China, for example, see Renishaw as an endorsement of their production quality. “To give them credibility, they are using our CNC controllers,” he adds. Throw in Renishaw’s probes, scale and read heads, and interferometers, and then factories can boast of their ‘accredited’ metrology systems. These come in useful when a factory wants to persuade a large blue-chip company, for example, that it can make components to the right standard.

Renishaw’s products are specialised equipment, which Sir David prefers to make in the UK for several reasons. He says: “We are producing high-value low-volume products that are complex to make. Unlike vacuum cleaners, say, these are not the sort of mass-produced item that you want to make abroad. Then there is the need to protect intellectual property rights (IPR). This is easier to do at home. For us, the UK is home to the all-important expertise in how you use that IPR.” The way to protect products, he explains, is not just through patents but how you make things, along with the processes involved and how you control them. “There are lots of things in our products that are not obvious when you strip them down.”

Sir David McMurtry FREng FRS with the Revo 5-axis measuring system. Renishaw’s measuring head and probe system has won many awards for innovation around the world including Germany, France, India and the UK

New business

Where does Renishaw go in its search for ideas that it can patent and use for new products? There are more than 200 patents bound in leather volumes behind SirDavid’s desk in the renovated mill building that is the Gloucestershire headquarters of Renishaw. Do manufacturers turn up with problems they want solved? Sir David says: “One thing that I always try to teach, now that I’m getting older, is never ask what the customer wants. if customers tell you about their problems, then they will also be telling everyone else. Then when you say, ‘Here is my solution to the problem’, you will get 10 people queuing up saying, ‘Look at my solution!’. And you end up in a beauty competition to sell your approach.”

“Instead of asking what the problems are,” Sir David advises, “It is best to get to understand what the company is doing.” Identify the problems yourself and come up with solutions to solve them. “You ask yourself: ‘Could I make the business better? Can I measure things better? Can I reduce the amount of scrap?’ Things like that. Then when you come up with a solution, you have got the patent and you are better off.”

This approach helps feed the company’s large R&D budget. “We spend somewhere from 15 to 18% of the turnover on research.” That percentage recently dipped, not because of any fall in the R&D budget but because the company’s sales rose so quickly that the engineering spending as a percentage of sales couldn’t keep up. “We can’t turn R&D on and off,” Sir David explains.

The company’s belief in R&D appeals to governments, which hold up Renishaw as a role model for other businesses. Sir David shrugs off this attention. Renishaw isn’t like most companies, he insists. It may have gone public in 1984, with shares traded on the London Stock Exchange, but the two founders, Sir David and John Deer, still control more than half the company. Unlike many public businesses, they do not have to listen too closely to the City. It isn’t that he regrets floating the business; it did allow Renishaw to put some eggs into other baskets and allowed him to pay off his mortgage. But the company has never been back to raise more money and has always been profitable.

Economic downturn

It is probably just as well that the City is in no position to make demands of Renishaw. The company’s progress has not been without a few hiccups. When the global economy imploded in 2008, Renishaw’s orders plummeted. Turnover dropped sharply, but this was nothing compared to the 80% fall in orders to the company’s Japanese customers. After a relentlessly profitable history, it suddenly made a loss. The company decided to cut staff numbers and had to act because it was legally required to give the workforce three months’ notice before it made any redundancies.

Almost as soon as it implemented the staff cuts, Renishaw’s business bounced back strongly although the recovery had nothing to do with the cuts. “It just happened,” Sir David explains. Had they not reduced the staff, the company might have lost money that year, but, thanks to owning most of its own property, Renishaw is asset-rich and could have survived. “If I had known that an upturn was coming you could have seen that as a mistake. But it certainly wasn’t a mistake when you are without the hindsight. I didn’t know how long it was going to go on.” Renishaw didn’t just cut back on staff during the recession, it also looked more seriously at markets beyond its traditional mainstays of aerospace and automotive companies. SirDavid says: “In particular, we noticed that the medical sector was still getting business”. So the company’s interest in medical markets increased. “It is a more stable platform when things go horribly wrong in the world”, and it is still in the company’s bailiwick. “If it is teeth, or if it is brain surgery, it is all precision engineering.” Renishaw’s healthcare products include, among other things, dental scanners, dental CAD/CAM systems, dental milling machines and neurosurgical robots. More recently, it has moved into additive manufacturing.

Such was Renishaw’s recovery from the economic slump that the workforce quickly overtook its former levels. The business went into the recession with around 2,300 workers, and redundancies brought this down to 1,850. Today, the workforce stands at 3,100, with 500recruits last year alone. In 2013, it expects to take on a record 40new apprentices. “We are planning for 64graduates next year as opposed to 32 this year.”

University research

Talk of graduates leads naturally to the role of universities. Sir David is not keen on a system that he sees as focusing universities towards research, rather than teaching more engineers, especially at a time that industry is experiencing significant skills shortages. “As a nation there is a lot of talk about re-engineering our economy to create more high-value manufacturing companies with an export bias, and yet we’re all facing the challenge of finding good people with specialist knowledge. Higher fees are at least driving students towards degrees such as engineering that will ultimately make them more employable, but there just aren’t enough additional places available to meet this increased demand.”

Like many others in the sector he warns of an impending skills crisis. “Given that the numbers of retiring engineers is greater than the number of new engineering graduates being produced, then, given the choice, Iwould like to see fewer government grants spent on research and more on educating graduate engineers.” He isn’t, though, among the chorus demanding ‘oven-ready graduates’ who can walk into a job and do everything from day one. “Teach them to a high level,” says Sir David, “and then industry will take them and mould them into its particular needs, because its needs vary dramatically”.

If universities didn’t do all that research, who would? “We have a poor record of turning university output into income for UK plc, and the lack of uptake of university blue sky research is a real problem,” says Sir David. “There has to be a greater understanding that ultimately it is industry that will drive the applied research and create a good return from the high-quality research that we do have in many of our universities.” He also believes that ownership and commercialisation of intellectual property arising from the research have to be clearly understood from the outset. “Let those of us with a good track record of making money from innovation take the lead.”

Playing the long game

Renishaw certainly has that track record. Even during the economic meltdown it made money. Sir David may not pay much attention to the City, but it has noticed what the company is doing, with a share price that, at the last count, is 65% higher than it was a year ago. And all this achieved by making things, with a long-term perspective. “We do long-term …” says Sir David, “… some of our products have taken 14 years to develop. We have stuck with it. But it is being paid for out of products that have taken equally long to develop and are now successful.” Development cycles that long may terrify the City, with its short attention span and demands for quick returns. But with another increased pre-tax profit of £86million last year, Sir David McMurtry, for one, will not be paying much attention.

Keep up-to-date with Ingenia for free

SubscribeOther content from Ingenia

Quick read

- Environment & sustainability

- Opinion

A young engineer’s perspective on the good, the bad and the ugly of COP27

- Environment & sustainability

- Issue 95

How do we pay for net zero technologies?

Quick read

- Transport

- Mechanical

- How I got here

Electrifying trains and STEMAZING outreach

- Civil & structural

- Environment & sustainability

- Issue 95