Supporting the digitally left behind

Consider not being able to pay your electricity bill, find the best deal for home or car insurance, manage health issues, submit a claim for social benefits or even buy things. All these everyday tasks, and many more, depend increasingly not just on having access to communication technology but on having the physical or mental ability and confidence to use services provided by digital technology.

As digital services become increasingly essential to society, and as cost-cutting closes traditional ways of fulfilling these tasks, many millions of people become members of the digitally left-behind community (the DLBC).

The DLBC exists because the entry level to the digital world is set too high for many

Being part of the DLBC is about more than accessibility to fast broadband or understanding how to use a mouse. The DLBC exists because the entry level to the digital world is set too high for many. The obstacles to effective interaction in a digital society are not simple and include:

- age

- physical issues

- technical complexity

- financial limitations

- trust

These obstacles grow by the day, as many of the agencies and businesses that the public has to deal with move their services from paper and personal contact to digital interfaces. Too often these new interfaces have been designed for people who can understand and afford the latest technology. Consequently, the bar is set too high for individuals who cannot, or do not want to, participate.

Engineering complexity is at the heart of the problem. Computer technology and the design of the applications that we use to access many services have created interfaces that many people simply cannot master or do not trust. The result of this growing ‘digital divide’ has been to create a three-tier population.

There is an elite community of people who are confident in, and early adopters of, digital services and can deal easily with complicated interfaces. Then there is what we can describe as the coping community of warily self-sufficient people who may be uneasy with the technology but who can use some applications. The bottom tier consists of the large DLBC, whose plight indirectly affects everyone.

The digital limitations of the ‘digitally challenged’ inhibit them from seeking and getting better jobs, simply applying for a driving or TV licence, accessing public services, booking a holiday and more. This handicap also applies to a significant number of younger people, whose digital capability amounts to little more than texting, gaming and emailing.

This approach should include bringing together the designers and engineers charged with building the digital services for online banking, government services, retail, and the many support groups already trying to help the DLBC

You might think that we have known about this challenge for ages, and that actions are in hand to fix the problem. In reality, accessibility and better broadband, the main focus of those actions, are not enough. We cannot address the DLBC’s needs without a full understanding of its makeup and aspirations. Without this understanding, digital designers will struggle to specify new user interfaces that tear down the barriers to access, thus creating a growing divide between the DLBC and the rest of society.

As engineers, we could start to tackle these barriers through using interdisciplinary systems thinking – an approach that looks at how a system’s parts interrelate, work over time and within the context of larger systems – coupled with broader user analysis, to come up with and validate sustainable solutions. This approach should include bringing together the designers and engineers charged with building the digital services for online banking, government services, retail, and the many support groups already trying to help the DLBC.

Only in this way can we begin to answer some of the many questions that need the be addressed. What does a dementia-friendly bank account look like? When will we be able to fill in a tax form with voice only? When will it cost pennies rather than tens of pounds to connect to the internet? When will the internet truly be easy for ‘dummies’ to use? When will most people safely trust the internet? How can we tackle, in a user-friendly way, the issues of trust and privacy, such as the removal of the physical assurance of cheques, identity theft, password proliferation and personal data security, not to mention unsolicited emails?.

What does a dementia-friendly bank account look like? When will we be able to fill in a tax form with voice only?

To mitigate this threat, we need to take some vital steps. To begin with, we need to understand the extent of the problem. One way to achieve this would be for the Office for National Statistics to work with academic researchers to establish the size of the DLBC population, whether this is increasing or decreasing, and the community’s societal and economic impact. A next step would be for the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport to take the lead in government and address the challenges in a systematic and properly resourced way.

There will also have to be R&D to create new approaches to bringing digital services to the DLBC. For this to happen, UK Research and Innovation should make an appropriate investment in understanding and addressing the needs of the DLBC.

The IT industry must also play a significant role in this process, by examining its own methods and thinking so that systems really meet the needs of everyone and not just the ‘digital elite’. Suppliers of systems and applications can also play a more effective and responsive role by collaborating on ways that make it easier for the DBLC to participate in the digital revolution.

It is perhaps also worth pointing out that the measures described would not just benefit the digitally disadvantaged. To pick just one example, everyone who has to complete an online tax form every year would welcome more user-friendly technology.

Establishing and reducing the size of the DLBC is very important for the community itself and for the economics of the IT marketplace and many of the businesses that use IT as a major channel for their products and services.

***

This article has been adapted from "Supporting the digitally left behind", which originally appeared in the print edition of Ingenia 76 (September 2018).

Contributors

Dan Bailey is the Public Sector Vice President at IBM. Before this, he was the Chief Technology Officer for IBM UK & Ireland Services. He has over 25 years of experiences in the IT industry, having worked across the globe in numerous industries.

Dr Maurice Perks is an independent consultant and a retired IBM Fellow, with more than 40 years’ experience in IT systems across several sectors. He spends one day a week helping the DLBC at an IT walk-in centre.

Chris Winter is an ambassador for the Digital Poverty Alliance. He was an independent IT consultant, IBM Fellow emeritus and Royal Academy of Engineering Visiting Professor at the University of Plymouth.

Keep up-to-date with Ingenia for free

SubscribeRelated content

Software & computer science

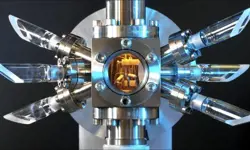

Compact atomic clocks

Over the last five decades, the passage of time has been defined by room-sized atomic clocks that are now stable to one second in 100 million years. Experts from the Time and Frequency Group and the past president of the Institute of Physics describe a new generation of miniature atomic clocks that promise the next revolution in timekeeping.

The rise and rise of GPUs

The technology used to bring 3D video games to the personal computer and to the mobile phone is to take on more computing duties. How have UK companies such as ARM and ImaginationTechnologies contributed to the movement?

EU clarifies the European parameters of data protection

The European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation, due for adoption this year, is intended to harmonise data protection laws across the EU. What are the engineering implications and legal ramifications of the new regulatory regime?

Evolving the internet

He may have given the world the technology that speeded up the internet, but in his next move, Professor Nick McKeown FREng plans to replace those networks he helped create.

Other content from Ingenia

Quick read

- Environment & sustainability

- Opinion

A young engineer’s perspective on the good, the bad and the ugly of COP27

- Environment & sustainability

- Issue 95

How do we pay for net zero technologies?

Quick read

- Transport

- Mechanical

- How I got here

Electrifying trains and STEMAZING outreach

- Civil & structural

- Environment & sustainability

- Issue 95