The outsider who changed the system

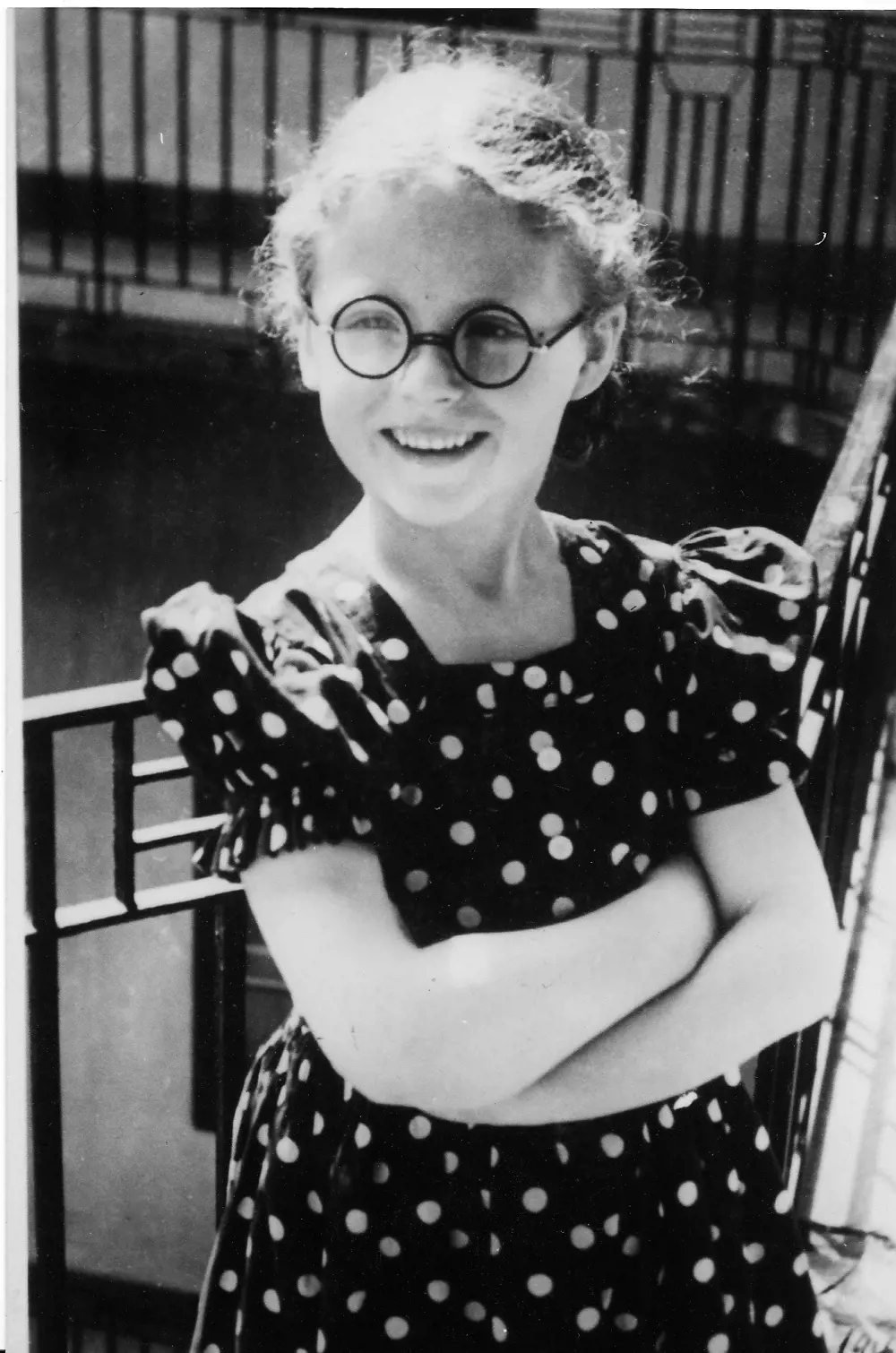

Agnes Kaposi as a six-year-old in September 1939, due to start school

Had it not been for the Hungarian Communist Party, Dr Agnes Kaposi FREng might have followed her interest in physics and maths and achieved her ambition to become a meteorologist. After the Second World War, the Communist party controlled everyone’s lives in Hungary and brushed aside her requests to study physics, telling her to study electrical engineering instead. Dr Kaposi warmed to the subject and ended up with a career that, after a troubled early life, led to her becoming one of the first women to be elected to the Royal Academy of Engineering.

In the event, she says she feels grateful to the “faceless Communist bureaucrats”. Meteorology might have been fun but so was engineering, and it proved to be a rewarding career.

Life was difficult enough in post-war Communist Hungary, but by then Dr Kaposi was used to hardship, having survived Germany’s invasion of her native country, and the Nazi Holocaust of the Second Word War. It would take a book to describe how she went from Holocaust survivor to being one of the UK’s leading engineers. Prompted by questions from her granddaughter,

Dr Kaposi has written that book, Yellow Star – Red Star, a richly illustrated autobiography and a fascinating account of Hungary’s mid-20th century history and politics.

Dr Kaposi recruited a distinguished historian, Dr László Csősz, senior archivist of the National Archives in Hungary, to provide a historical narrative and to “fact check” her recollections.

In the title of the book, ‘Yellow Star’ refers to Dr Kaposi’s Jewish childhood before and during the Second World War. Hungary’s antisemitism, and some of the country’s numerous anti-Jewish laws, predated the rise of Hitler. Dr Kaposi recalls how those laws affected her family, although as a child, she barely knew that they were Jewish – they hadn’t been actively religious, and her parents had no affiliation to any synagogue. She was more aware of her parents’ socialist leanings than their religion.

Dr Kaposi describes 1939 as a “memorable year”. It would have been for any six-year-old due to start school just days after the start of the Second World War. Anti-Jewish laws caused unemployment and poverty and antisemitic propaganda even penetrated the classroom, but the real impact of Nazism came when the German army occupied Allied Hungary in March 1944. Within weeks, Hungary’s Jews were compelled to wear the yellow star as a means of identification and were crowded into ghettoes in preparation for mass deportation to Auschwitz. Half of Dr Kaposi’s family perished, as did more than half of Hungary’s Jews. She and some of her family survived: theirs was the only Auschwitz-bound train diverted to Austria where they worked and starved in labour camps as farmers, factory workers and manual labourers.

Liberation by the Soviet army brought its own traumas. It took a month for surviving members of the emaciated family to cover the 150-mile journey, mostly on foot, from their camp near Vienna to a ruined Budapest. They never regained their home or their possessions, but they found an empty flat in a nearby town where all the local Jews had been murdered.

Dr Kaposi relates: “I got back from the camp on 1 May 1945 and on 2 May, hungry, without hair, without proper clothing, without a book, a pencil or a pen, I was at school. This is the way that I was brought up, the way my father trained me. Education was top priority. If I got home with 95% of the marks, I needed to account for what had been amiss.”

In the event, she says she feels grateful to the “faceless Communist bureaucrats”. Meteorology might have been fun but so was engineering, and it proved to be a rewarding career.

University engineer

No surprise then, that Dr Kaposi excelled at school and in 1951 went on to university. For a brief period immediately after the war, Hungary was a multi-party parliamentary democracy, but by 1949 the country became a one-party state, the ‘Red Star’ era described in Dr Kaposi’s autobiography. Communist tyranny deprived people of choice. Her boyfriend John loved gadgets, was a master of tools and machines, and was the “complete engineer”, graduating just before Dr Kaposi started university. Dr Kaposi had no interest in tools, machines and gadgets, but the Hungarian Communist Party sent her to study engineering in Budapest. She only just managed to escape from another future: thanks to subterfuge by a concerned teacher, she narrowly avoided spending four years studying in the Soviet Union.

After marrying at the end of Dr Kaposi’s first year at university, she and John graduated from the same electrical/electronic engineering course: John with a ‘good enough’ degree and Dr Kaposi with top honours. Yet, he would jokingly tease his wife throughout their 60-year marriage that she would never become an engineer.

The Technical University of Budapest was a revered institution. Dr Kaposi did well, but was an outsider from the start, “at sea” as she puts it. Why did they introduce different specialisms of engineering independently of each other, rather than teach fundamental principles of engineering and then apply those to different branches of the subject? She explains her thinking with an example. The course covered vibration in mechanical structures and other fields, such as acoustics. Bridges don’t look much like loudspeakers but the two have a lot in common. “The frequencies and amplitudes of vibration were different, but those are just parameters; the equations were the same,” she explains. “I couldn’t understand why we were learning the same equations several times over.” She plucked up the courage to ask her professors, but they told her to just get on with it. As an 18-year-old she did what she was told but later in life she decided to investigate the challenge she had thrown at her professors. Maybe she could tackle problems reasoning from the general to the particular. This approach helped her make the change from vacuum-tube-based electronics to transistor circuits, from analogue to digital communications, from switching theory learned in telephony to its use in computing. It also kickstarted her development of a discipline that came to be known as systems engineering.

As an undergraduate Dr Kaposi was lucky to be given an exciting degree project, supervised by Dr Béla Julesz, celebrated visual neuroscientist and experimental psychologist. The project was theoretically demanding and practically important: devising the nationwide transmitter/receiver network for a hybrid communication system to provide TV/telephone services for the whole country. The experience would come in useful later when Dr Kaposi arrived in the UK.

On graduating in May 1956, the Communist party commanded Agnes to take up the post of junior development engineer in EMG, a company that designed and manufactured electronic instruments for the Communist bloc. Sampling oscilloscopes were advanced instruments and working on their design was exciting, but Dr Kaposi’s career at EMG was short: in six months her whole life was to change.

A new start

October 1956 brought Hungary’s failed uprising against Communist rule. The chaos following offered an opportunity for Dr Kaposi and John to leave. They were keen to find freedom, have a normal life and start a family. So, they joined 180,000 others who fled Hungary and left the country illegally. In yet another journey of cross-country treks and uncertain train rides that would make a good film, the pair travelled across Europe. Their intended destination was Britain, but at the Paris stage of their journey the British Embassy turned them down on the grounds that they were only offering asylum to those still in Austria. After more than 150 job applications, the couple finally received offers from Pye in Cambridge where John, a radar technologist, designed circuits for the new colour television, while Dr Kaposi had a chance to continue her undergraduate work on multichannel television networks.

Their next move was to Ericsson Telephones in Nottingham where they each took charge of the design of a subsystem of the first electronic telephone exchange to be introduced in the UK and throughout the Commonwealth. Computers were the next step, and Dr Kaposi and John moved to the R&D Laboratories of ICL, among the first generation of computer engineers. However, the British computer industry was shrinking and there were frustrations.

Women in engineering

The role of women in engineering has been a constant issue for Dr Kaposi throughout her career. Comparing the position of women in Communist and western countries was the subject of her 1972 Churchill Fellowship, taking Hungary as an example of one, the US and the UK as the other. She found that under pressure of the Communist Party, a larger percentage of women studied engineering at university in Hungary than in the UK or in the US, but there was almost equal paucity of women engineers in senior positions in the east and west. Her findings date back half a century, but she suspects that even today, women engineers as senior decision-makers might still be outsiders.

A move to academia

In 1964 Dr Kaposi left ICL but maintained contact with industrial research through the rest of her career. Her first significant post was as a senior lecturer at Kingston Polytechnic – now Kingston University. Once again, she was an outsider. “I knew nothing about the British education system,” she says. “I had never been to a British school and didn’t know the difference between university and polytechnic.” Although she did know about computing, which had yet to be covered in engineering courses. Kingston was a good place to try new ideas. With her research experience and her PhD completed, Dr Kaposi wanted to devise a course to meet the increasing demand for IT skills. Her master’s degree course was innovative in content, mode of delivery and student population. It was an immediate success: scientists, engineers and mathematicians in senior and mid-career posts in industry, business and government queued up to join, seeking to bring the benefits of this new technology to their jobs. “Even now, I am proud of that course,” she recalls.

Dr Kaposi is, she says, “very proud” of her part in getting the British Computer Society to become a recognised as a professional engineering institution. “They applied and my colleagues were saying ‘they are not engineers, they don’t know any physics’.” By then, she was well known in the engineering world, but still had to enlist the support of eminent names that the engineering community could not ignore © Jay Kaposi

Change-maker

The success of the Kingston course persuaded Dr Kaposi that she could take on the bigger challenge of running her own department. Her next move was to South Bank Polytechnic – now London South Bank University – as Head of Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering. This had once been a centre of excellence of electrification and power engineering, supported by the Electricity Board and the power industry, but demand for these subjects had dwindled, industrial support was no longer forthcoming, and staff almost outnumbered students. Dr Kaposi was in a good position to rescue such a department, but here again, she was an outsider. Her staff, middle-aged and all male, told her that she had fallen victim to the passing fashion of computers, which were “here today and gone tomorrow”. They said it was nothing short of ‘vandalism’ making room for computers by removing some of the underused bulky power engineering equipment from laboratories. Perhaps upset that they hadn’t got the top job, some made it clear that they disliked having a woman in charge. “The woman’s place is in the kitchen,” is how Dr Kaposi recalls a lunchtime comment by a member of staff. That attitude seems less surprising when you learn that this was a few years before the International Journal of Electrical Engineering Education conducted a national survey showing that just 15 women, out of a total of around 1,600 academics, taught degree-level electrical and electronic engineering. Dr Kaposi was the only woman to head a department.

Dr Kaposi learned that it would take two years to navigate the purchasing bureaucracy before she could buy the first computer for her department. She contacted the local Chamber of Commerce. “Do your businesses need some computing skills?” she asked. Receiving an enthusiastic answer, she invited potential participants to pay upfront for short courses. She employed postgraduate students from Imperial College London as teaching staff. Computers arrived, a first step towards the review and modernisation of the curriculum.

Just then, engineering institutions introduced course accreditation. The intention was only to accredit full-time courses. Gaining the support of her staff, Dr Kaposi challenged the accreditors, refusing to submit South Bank’s full-time course for accreditation unless the part-time course was also considered. She argued that the part-timers were superb students: “It was a privilege to teach them because they were dedicated to learning and they benefited staff by bringing in insight of current industrial practice.” Professor Ewart Farvis of Edinburgh, IEE’s senior accreditor, understood the argument; he had himself started his career as an apprentice. With his support, South Bank’s Electrical and Electronic Engineering department gained equal recognition of its full-time and part-time courses. This was a turning point for the department. Student numbers started to rise, new, younger staff could be recruited, and course review could be devised and implemented. A surprising additional result was that IEE’s accreditation committee invited Dr Kaposi to join it as the only woman and the only polytechnic head.

Word about the courses at South Bank spread. The Manpower Services Commission heard about the department’s computing-oriented course curriculum and saw this as a possible answer to a current problem of graduate unemployment. It offered funding and sponsorship and, in response, Dr Kaposi devised several courses: routes to industrial jobs for unemployed graduates. “At first, only holders of a first- or second-class degree in science or engineering qualified for entry into our master’s course, but to aid graduates with good degrees in other disciplines, we offered an industrially sponsored preparatory conversion course in mathematics and laboratory work.” Dr Kaposi believes that, with its 200 postgraduate students, her department was running one of the largest graduate schools in the country.

Funded by the Manpower Services Commission and with special dispensation from the European Community, the department also offered a one-year intensive course for unemployed women graduates, leading to a Higher National Certificate (HNC) qualification. To convince employers of their equal value to industry, these women took the same qualifying examinations as the men on the department’s well-established HNC course. “We served the local and the wider community, giving a chance to men and women to reach their full potential. I speak about this with socialist pride.”

A decade on from Dr Kaposi’s arrival at South Bank, the department was thriving, student numbers were well above 1,000, the undergraduate and postgraduate curriculums were up to date, and there was a flourishing research school, funded by industry, the Research Council and the European Commission. The old guard had moved into line or had retired, and the young staff were more than able to provide the energy and initiative to augur a safe future. Dr Kaposi felt that the time had come for her to move on.

Career timeline and distinctions

Born, 1932. Studied electrical/electronic engineering at the Technical University of Budapest, 1951–1956. Junior development engineer, EMG Budapest, 1956. Development engineer, Pye Ltd, 1957. Senior R&D engineer, Ericsson Telephones, 1958–1961. Principal R&D engineer, International Computers Limited, 1962–1965. Senior Lecturer/Principal Lecturer, Kingston Polytechnic (now Kingston University), 1966–1976. Head of Department, Electrical/Electronic Engineering, South Bank Polytechnic (now London South Bank University), 1977–1987. Churchill Fellow, Women in Engineering, 1972. Partner, Kaposi Associates, and Director, Kaposi Associates Ltd, 1988–2009. Fellow, Royal Academy of Engineering, 1992. Published autobiography, Yellow Star – Red Star, 2020.

System of systems

Throughout her academic career, Dr Kaposi worked as a researcher and industrial consultant. Her research work extended from computer-aided design and software engineering to methodological foundations for systems engineering, captured in two of her books: Systems, Models and Measures and Systems for All, written in collaboration with one of her PhD students. Interest in her research created demand for consultancy services. While still at Kingston, her clients included Plessey Radar, which then went on to sponsor Dr Kaposi’s PhD; Imperial Tobacco; and Rank Xerox, for whom she designed small special-purpose computers, embedded in the company’s machinery for years. Other clients needed support for a series of projects, such as the Admiralty Surface Weapons Establishment and AT&T Europe in Stuttgart, Antwerp and Paris. Three sabbatical months at BT’s Systems Research Division at Martlesham led to several years of consultancy engagement with branches of BT.

After leaving South Bank, Dr Kaposi set up a full-time consultancy business in partnership with John and a resident IT specialist from Imperial College London. Using the methodological handle of systems engineering and drawing on their network of industrial and academic contacts, they created bespoke teams to tackle various projects for a wide range of clients, such as Siemens in Brazil and Germany, two international banks, and quality certification agencies in two European countries. They also acted as advisors on staff development and curriculum review to several universities in the UK and Europe. With undimmed socialist convictions, Dr Kaposi remarks with some regret that full-time consultancy was far more lucrative than an academic career. The business thrived for over a decade, until John became too ill to work and passed away.

That was when Dr Kaposi finally gave in to her family’s demands to record her life story. Even here, she took an engineer’s approach. “I knew the difference between remembering something and knowing something about it, or knowing it properly and having the authority to write it down for publication. There was a lot of research to be done.” Her book Yellow Star – Red Star took 10 years to write. She visited libraries, museums and historical sites, searched through books and documents, looked for advice from fellow Holocaust survivors, and sought support from historians. It was the director of London’s Wiener Library who suggested the historian Dr Csősz as a collaborator. This settled the format of the book: narrative of a witness, authenticated by the voice of a historian.

Nowadays, Dr Kaposi is a busy educator with engagements reaching two years ahead. Her approach to history is the framework for her presentations. Her main concern is that people have failed to learn the lessons of the past, so intolerance increases, violence persists, injustices sharpen, and minorities continue to struggle under tyranny. The need to learn from the Holocaust has become more pressing as the number of survivors dwindles. Dr Kaposi agrees that there is a need for the second and third generation to tell the story of the Holocaust, but she has reservations about this, and explains her concerns with an engineering parallel. “An engineer would know that, from source of information to recipient, there is the danger of cumulative distortion and interference.”

***

This article has been adapted from "An outsider who changed the system", which originally appeared in the print edition of Ingenia 88 (September 2021).

Contributors

Michael Kenward OBE

Author

Keep up-to-date with Ingenia for free

SubscribeRelated content

Electricals & electronics

Accelerometers

Used in earthquake measurements, laptops, planes and even in stargazing apps, today’s accelerometers are much smaller than when they were first developed in 1927. Find out how they detect movement and vibration.

How to maximise loudspeaker quality

Ingenia asked Dr Jack Oclee-Brown, Head of Acoustics at KEF Audio, to outline the considerations that audio engineers need to make when developing high-quality speakers.

Cable fault locator

The winner of the Institute of Engineering and Technology’s 2014 Innovation Award was EA Technology’s CableSnifferTM, which uses a probe and chemical sensing technology to identify faults, saving energy companies millions of pounds each year.

High speed evolution

In December 2010, Eurostar International Ltd awarded a contract for 10 new high speed trains to Siemens. The company has used a system developed over decades to maximise the performance and passenger-carrying ability of its 320km/h trains.

Other content from Ingenia

Quick read

- Environment & sustainability

- Opinion

A young engineer’s perspective on the good, the bad and the ugly of COP27

- Environment & sustainability

- Issue 95

How do we pay for net zero technologies?

Quick read

- Transport

- Mechanical

- How I got here

Electrifying trains and STEMAZING outreach

- Civil & structural

- Environment & sustainability

- Issue 95