How do we pay for net zero technologies?

What is green investment?

Over the past decade, financial markets have warmed to the concept of ‘green investment’ – investment that has a stated positive environmental contribution. Investment in ‘clean tech’ is now a mainstream activity, especially for established technologies such as wind energy and solar photovoltaic power generation.

This growing enthusiasm for green finance has led to new ways for investors to ensure that the ventures that they back really are sustainable technologies that can contribute to the quest for ‘net zero’. The investment profession has its own well-developed terminology and approach to managing risk and opportunity. While these approaches cover commercial and technical considerations, the rise of green investment means that there is increasing overlap with environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors.

Responsible vs. sustainable investment

Responsible investment, as a more general term, involves comprehensive and prudent management of ESG considerations to deliver long-term economic returns. It minimises harm to stakeholders and the environment, and transparently discloses environmental and social impacts and outcomes of the investment.

Sustainable investment includes the above and goes further by pursuing specific sustainability goals, actively investing to drive a transition to long-term ESG sustainability.

The growth of green investment has seen widespread use of the terms ‘responsible investment’ and ‘sustainable investment’. In practice, each label has a distinct focus that becomes important as we look to finance net zero engineering and to make the UK an internationally attractive investment hub for net zero technologies and services.

A growing enthusiasm for green finance has led to new ways for investors to ensure that the ventures that they back really are sustainable technologies that can contribute to the quest for ‘net zero’.

How the UK government is supporting green investment

The government is developing mechanisms to support green investment, with the aim of making the UK an internationally attractive investment hub for net zero technologies and services, as well as a ‘net zero aligned’ finance centre.

A range of actions address international and national obligations. These include:

- aligning financial institutions with net zero ambitions

- updating national green finance strategy to signal UK leadership

- encouraging private sector investment

- support for emerging markets.

To build confidence in the delivery of auditable and sustainable outcomes, much of the effort is on transparent disclosure and financial reporting to accepted and newly developed standards.

Why is green investment important in the UK?

Mission Zero, the government’s Independent Review of Net Zero, published in January 2023, recognised the UK as a world-class supplier of environmental goods and services, including clean tech and green finance. It also points out that the UK is well placed to take advantage of the comparative advantages it has over other advanced economies. It acknowledges this sector’s key role in paving the way to sustainable economic growth in the UK.

Taking energy supply as an example, policy on the energy sector’s transition to net zero is driven by the need to balance sustainability, energy security and reliability, and affordability. Achieving this balance requires the sustainability, engineering and finance professional communities to collaborate. These communities have much to learn about each other’s ways of working and the factors that determine good decision-making.

The UK has also recently upgraded its Green Finance Strategy, which aims to drive investment in green tech to deliver the country’s energy security, net zero and environmental objectives (See ‘Supporting green investment’).

© This is Engineering

Investor perspectives: risk, return and TRLs

Investors will support a new technology where they believe that there will be a return on investment. The investment sector uses the terms bankability or ‘investability’ to demonstrate willingness to finance a technology after considering risks and returns. Investors need to understand how a new technology is likely to perform in both engineering and financial terms. Investors have differing expectations of risk-taking and of the magnitude and timing of the financial returns they expect.

Investors will take different approaches, depending on which of the two markets they invest in: public markets (listed stock exchanges, government bonds, or public commodities) or private markets (property, infrastructure, or private equity venture capital). They will most likely consider the countries where the investment happens and the countries’ regulations, as well as their own ability to control the companies they invest in, for example by taking >50% controlling equity stakes versus a minority investment or through lending.

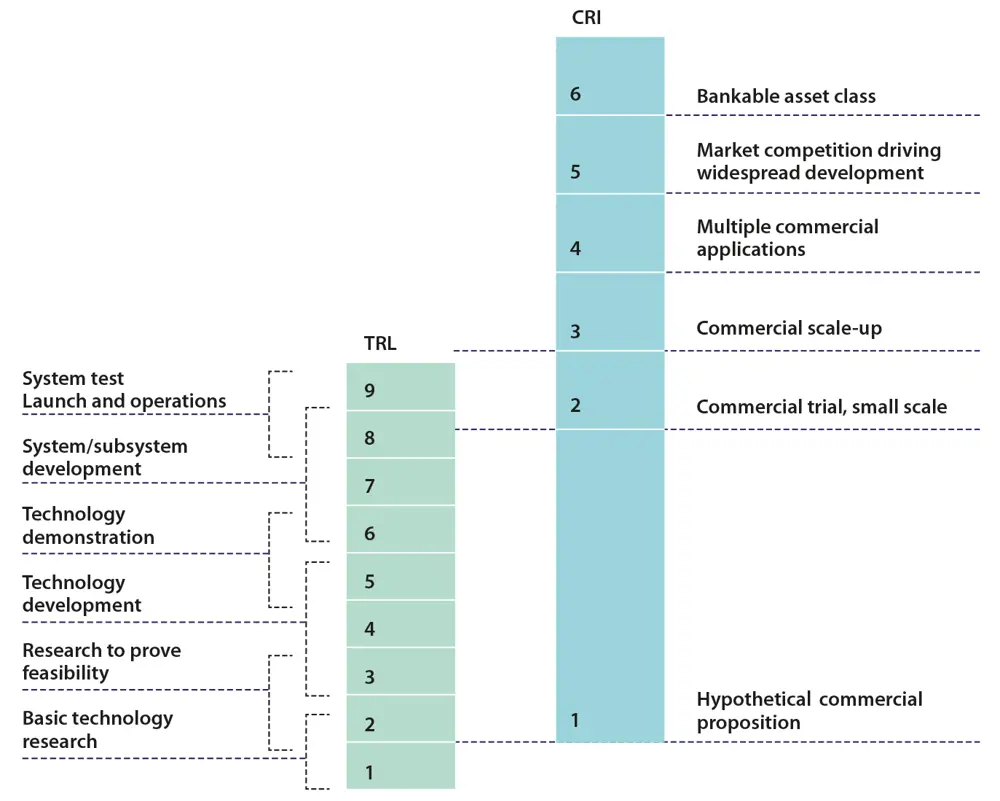

Before they back any venture, investors will want some idea of a technology’s readiness for investment. One way to demonstrate this is through processes such as the assessment of technology readiness levels (TRLs). Developed by NASA in the 1970s, TRLs offer a nine-level framework for classifying technologies (see figure below). Using frameworks like these, potential funders – including publicly funded technology incubators, grant funding bodies, venture capital or ‘angel’ investors, or fully commercial equity investors and lenders – can then define their willingness to invest in technologies at different stages of commercial viability.

Ways to analyse the commercial potential of new ideas include the assessment of technology readiness levels (TRL) and commercial readiness index (CRI) (adapted from the Australian Renewable Energy Agency’s report Commercial Readiness Index for Renewable Energy Sectors)

Technical due diligence in green investments

Through TV programmes such as Dragon’s Den, we have become familiar with scrutinising new business ideas and the claims made for them. When looking at technologies beyond the fundamentals of proof of concept, intellectual property and market demand, investors may call upon support from engineering specialists for more detailed due diligence.

This can include engineering input on:

- fundamentals of engineering design

- configuration of unit processes and their individual and combined performance

- project management aspects

- the environmental and technical suitability of proposed site

- safety

- securing regulatory permits

- technology performance in the early stages of implementation

- the acquisition and analysis of reliability data when technologies are in service.

Investors assess these factors as the basis for a robust evaluation of a ‘risk-adjusted return on investment’. Assessments may extend beyond the feasibility of a pilot or near-industrial scale trial, to a full-scale application. Assessments may also involve considering supply chain risks; for example, for bespoke engineering components provided by only one or two suppliers globally; or subassemblies with specific warranties; or the examination of financial models that detail how profits are generated. Then there are maintenance agreements to ensure long-term reliability.

Investors may also seek opinions on a company’s organisation, its governance, and its commercial and technical abilities. Where investors use other people’s money for the investment – say from pension funds or through banks – the investor has a ‘fiduciary duty’ to act in the best interests of the beneficiary. It must then align the investment to the beneficiaries’ appetite for risk. Without due diligence, there could be misalignment between these interests and an investment manager could run the risk of regulatory action.

Anaerobic digestion

Anaerobic digestion (AD) technology produces bioenergy from organic wastes that would have historically gone to landfill or been spread on land. AD uses natural processes within engineered containers where microorganisms convert waste material from plants or animals into useful products in the absence of air.

The biogas produced is typically a mixture of 60% methane and 40% carbon dioxide by volume. Biogas can provide heat, electrical power or a biomethane as a transport fuel. AD first attracted investors because of its potential to offer long-term municipal green waste contracts combined with the possibility of supplying energy to the grid.

The bankability of investment in AD has focused on features such as set-up costs, availability of technical expertise, project management, the feedstock flows to and from waste catchment, the time taken to ramp up to full-scale operation and hence security over revenues, and the engineering performance of the technology in its various forms.

A biogas production plant © Gerald Krieseler / Pixabay

Navigating complexity in new technologies

These factors underline the complexity of financing new technologies that claim to contribute to net zero. Independent technical appraisal has become critical in assessing engineering innovations such as anaerobic digestion technologies (see ‘Anaerobic digestion’), biogas, hydrogen, and energy storage. The issue is complicated by the rapid arrival of many new commercial players with competing technology claims. Investors need greater confidence, and, because of an uncertainty in technical success, may look to share risk in earlier investment stages.

Also, investors look to reduce how long it takes to pay back debt, or to schedule pay back more frequently as a contingency against suboptimal technology performance. They can also insist on building up reserves to pay for periodic maintenance. There have also been suggestions that the bankability of climate change projects and technologies should align to national policies, investment fund priorities and should secure local community support. The ‘hydrogen economy’ could face such challenges as it takes off.

R&D projects may need initial public investment to demonstrate technical viability and stakeholder confidence before attracting private finance at later stages. Such approaches to due diligence have been applied for decades. However, the changing nature of investment means that investors place increased importance on ESG issues and claims about sustainable development.

How engineers can help validate sustainability claims

Engineering technologies that can drive a low-carbon transition offer specific outcomes for carbon reduction and related goals. While this aligns them to sustainable investment goals, unless sustainable outcomes can be backed up with reliable evidence, unsupported claims, or ‘greenwash’ could cast doubts on the credibility of the green finance market. Investors need evidence to validate claims of ‘sustainability’ before a technology is eligible for investment from pools of capital earmarked for green investment.

Green financing for projects that contribute to our net zero ambitions is gathering pace, alongside a developing tapestry of regulations, reporting standards and guidance for investors. As this continues, there will be a growing demand for in-depth technology appraisals.

Glossary

- Asset: in financial terms, anything that holds current or future value for a business; asset classes being, for example, specific classes of clean technologies.

- Emerging markets: new market opportunities often characterised by disruptive novelty, fast growth and an uncertainty in returns.

- Green finance: a loan or investment, whether from public or private sources, used to support environmentally sustainable activity.

- Net zero engineering: engineering approaches to securing a balance between the amount of greenhouse gases produced and the amount removed from the atmosphere.

- Risk premium, or default risk premium: often, an extra amount of interest paid to an investor by the borrower as compensation, say, for the uncertainty in technology performance and thereby pay back of the investment.

Furthermore, the range and complexity of issues that investors and lenders now have to address on investments in clean tech is increasing as a result of higher expectations from shareholders, pension fund beneficiaries, bank depositors, and other sources of capital.

Then there is the development of more demanding regulation and rising expectations from society at large. To meet these demands for technical advice, the finance sector will increasingly draw on engineers and sustainability professionals. In turn, engineers will need to understand the issues that face the world of finance.

***

This has been adapted from "Accounting for net zero", which originally appeared in the print edition of Ingenia 95, June 2023.

Contributors

Adrian Barnes joined the UK Green Investment Bank in 2013 from a background in environmental consultancy. A key figure in the UK green finance sector with Macquarie Asset Management’s Green Investment Group, Adrian contributes to emerging ISO standards on green finance, and on harmonising greenhouse gas assessments between financial institutions.

Professor Simon Pollard OBE FREng is a Pro-Vice-Chancellor at Cranfield University and an environmental engineer specialising in risk management. He is a frequent commentor on the green economy and a Non-Executive Director of the Institute of Environmental Management and Assessment.

Keep up-to-date with Ingenia for free

SubscribeRelated content

Environment & sustainability

Recycling household waste

The percentage of waste recycled in the UK has risen rapidly over the past 20 years, thanks to breakthroughs in the way waste is processed. Find out about what happens to household waste and recent technological developments in the UK.

Upgrade existing buildings to reduce emissions

Much of the UK’s existing buildings predate modern energy standards. Patrick Bellew of Atelier Ten, a company that pioneered environmental innovations, suggests that a National Infrastructure Project is needed to tackle waste and inefficiency.

An appetite for oil

The Gobbler boat’s compact and lightweight dimensions coupled with complex oil-skimming technology provide a safer and more effective way of containing and cleaning up oil spills, both in harbour and at sea.

Future-proofing the next generation of wind turbine blades

Before deploying new equipment in an offshore environment, testing is vital and can reduce the time and cost of manufacturing longer blades. Replicating the harsh conditions within the confines of a test hall requires access to specialist, purpose-built facilities.

Other content from Ingenia

Quick read

- Environment & sustainability

- Opinion

A young engineer’s perspective on the good, the bad and the ugly of COP27

Quick read

- Transport

- Mechanical

- How I got here

Electrifying trains and STEMAZING outreach

- Civil & structural

- Environment & sustainability

- Issue 95

Building with fungi

- Aerospace

- Electricals & electronics

- Issue 95