The journey to portable dialysis

“Everybody thinks I’m a physicist but I’m a mechanical engineer,” insists Professor Clive Buckberry FREng. The misconception is understandable, given his previous role as head of vehicle physics at BMW. “I always wanted to do engineering design,” he says. It all started because he was good at technical drawing. When he joined Rover/ BMW after graduating, he soon learned that physics provided him with many of the tools that he needed to understand engineering challenges.

“Physics underpins most of mechanical engineering," he says. "I never talk in terms of engineering. I usually bring it back to first principles. Then I do experiments, to validate the theory, usually in the lab.” Over the years, Clive has used this approach to understand engineering challenges from the noise and vibration in cars to the operation of machines for kidney dialysis.

He admits that his engineering career didn’t get off to a flying start. His school exam results weren’t good enough to guarantee him a college place. Fortunately, he had a training job at local engineering company, which agreed to sponsor a place at college. So, when he rang the college to tell them he had got two Es instead of two Ds (as well as a B in technical drawing, his favourite subject), but still had sponsorship, they told him to come in and give it a go. If it didn’t work out, he could switch to a higher national diploma (HND). “It was literally that conversation – I remember, at 10am in the morning – that gave me a passport to the future.” In the event, he got on just fine at Trent.

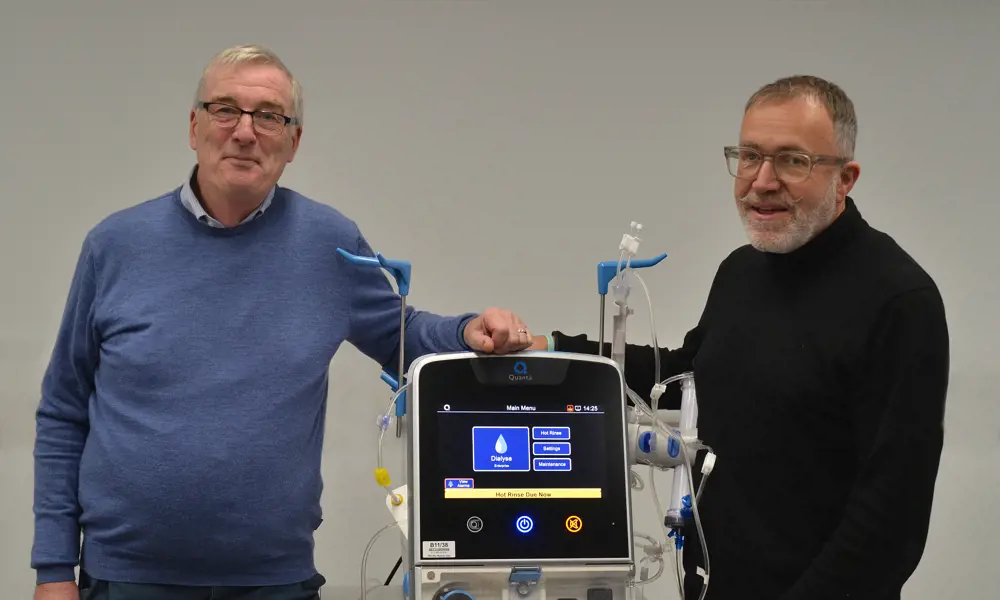

Professor Clive Buckberry FREng shares the development journey of an award-winning dialysis system.

Clive recounts his early experience not just to explain how he got where he is today, as Chief Engineer and Technology Officer of Quanta Dialysis Technology, but to reflect on the current state of engineering education. “Could you imagine that happening now? There’s an emphasis on getting the best grades and everybody wants to go to a Russell Group university. And they have to pay; I got paid to go.” The government’s investment paid off. Clive emerged with an honours degree in mechanical engineering, followed by an ‘MTech’ in engineering design at Loughborough University. His degrees got him a job with Rover Group, then a part of BMW. His first thought had been a career as a design engineer, working on new cars. “I got to the design studio at Rover and they were doing some fantastic things there.” They had even won the Royal Academy of Engineering’s MacRobert Award, he recalls. But the thought crossed his mind that he could get pigeonholed in design. “I can almost remember thinking, actually I’m going to be a door-handle designer for 40 years.”

Making the move from design to physics

Clive began to use physics to understand and solve engineering problems. He worked as a Technical Manager in the Applied Optics Laboratory at Gaydon – Jaguar Land Rover's R&D facility. “I did lots of work with holography,” he explains. These were the early days of applying lasers to engineering. Thirty years ago, you almost had to have a physics degree to use the tools. “It was quite fundamental work. People just thought I was a physicist.” With no academic training in physics, he says, “I always had to go back to first principles. That’s when I started to ask physics-type questions.”

The team at Gaydon was picking up on earlier work by VW’s engineers on vibration using “a large ruby laser”. The optics team studied a range of topics, including vibration in car bodies, windscreens, and brakes alongside Heriot-Watt University. In one project, it made transparent engines out of sapphire so that their optical techniques could compare real-world measurements with computational fluid dynamics (CFD) models. Clive delights in explaining that it resulted in a successful sponsored PhD project at Loughborough University. The academic research took about three months, he says, followed by three years deciding what to write up.

The group also pioneered the use of lasers and fibre optics to measure stresses and strains in car bodies and components in what are called ‘speckle interferograms’. Clive turned some of this work into his own PhD at Cranfield University on real-time speckle pattern interferometry. The university also allowed him to do the research in industry rather than on campus. “I could still do the day job, and then do the PhD in the evening.” This was a new approach at the time, that has now become commonplace.

Physics underpins most of mechanical engineering. I never talk in terms of engineering. I usually bring it back to first principles. Then I do experiments, to validate the theory, usually in the lab.

Professor Clive Buckberry FREng

Around this time, Clive was drawing on his background and ability to draw to refine his approach to ‘selling’ the engineers’ work to managers. “To get management to buy into something, a picture paints 1,000 words, particularly for engineers. We always used to say at BMW that if you show them a colour picture in real time of complex behaviour, they’ll sign it off.” His passion for visualising pervades his approach to solving engineering challenges. “I think of how lucky I was just being able to draw.” He traces some of that back to his degree course in engineering design. “It’s not so much about STEM – science, technology, engineering, and medicine,” he explains, “it’s about STEAM.” The A is the arts, the creative element. “You need that inventive, creative bit to make the rest of it work, in any industry.”

Clive eventually led a department of about 120 people at BMW, responsible for aerodynamics and acoustics. But he then faced a decision. When BMW decided to divest itself of the Rover business, Clive was invited to relocate to Germany. By then he was embedded in the uses of physics, especially optics, and had the chance to become engineering director at Melles Griot, a company that specialised in lasers and optics.

Shortly after, he then faced another choice: move to Cambridge with the company or stay near his wife’s family in Warwick. Confident that he’d find something to do, they decided to stay. A job ad took him to a company called IMI Vision, an in-house ideas operation tasked with helping its parent company, IMI Plc, one of the UK’s leading engineering businesses.

Quick Q&A

BBC science programmes started Clive on the path to becoming an engineer

What inspired you to become an engineer?

Watching Tomorrow’s World and Horizon on the BBC as a child.

Favourite project you’ve worked on?

Rover K-series optical engine with full access for laser-based imaging of combustion.

What are you most proud of?

Creating Quanta from the initial ceremonial exchange of £1 to raising more than £400 million of investment.

What’s your advice to budding engineers?

Ask lots of questions and don’t be afraid to do the experiment and get it wrong the first time trying.

Best bit of the job now?

The sheer variety across engineering, production to clinical application.

Which engineering achievement couldn’t you do without?

My glasses.

Most impressive bit of engineering to look at?

Stonehenge.

What do you do in your spare time?

Astronomy with my 18-inch Dobsonian telescope and tinkering with my Manx Triton motorbike.

IMI was active in many different sectors that could use engineering input. One business area was machinery for dispensing soft drinks. It was Clive's and others work in this area that laid the foundations for the dialysis machine that won the 2022 MacRobert Award. It was one of the projects that IMI Vision hoped to turn into a new business. IMI already made dialysis machines under licence. It wanted to move up the food chain and devise its own machine. That meant going back to the components and looking for a better way of, for example, cleaning valves that got clogged up with deposits during dialysis. This was true teamwork, with attention to the laws of physics playing a key part. Looking for a solution to the problem of clogged valves, Keith Heyes, an original member of the project team, remarked: ‘Well, you can’t beat the laws of physics. You’re always going to get precipitation.” The team already had a solution to hand: use disposable components based on valves made for orange juice dispensers. The project was ultimately spun-out from IMI to create a new company, Quanta Dialysis Technologies.

Clive used his ability to visualise what is happening when he wanted to understand the inner workings of the dialysis machines made by Quanta Dialysis Technologies (Kidney dialysis – the take-home option, Ingenia 62). “One of the things we did with the dialysis machine – to get it to work and understand how the cartridge worked – was making a machine with a transparent door. The cartridge is transparent, so we could then see the fluid flows within.”

Quanta won the MacRobert Award for the SC+, a compact and portable dialysis machine “allowing more flexible and accessible care for patients with renal failure”. As Professor Sir Richard Friend FREng FRS, Chair of the MacRobert Award judging panel, said: “Recent success comes on the back of Quanta’s considerable journey as a company.” As he put it the success took “persistence, innovation and unconventional thinking”.

The MacRobert Award-winning team at the Royal Academy of Engineering’s Awards Dinner in 2022. The new award joins Clive's RAC Dewar Trophy from 1995 for advances in automotive industry technology. As he says, there can’t be many engineers who have collected two such leading awards in such diverse industries as automobiles and medical technology. “For someone who has got no A levels per se. I’m quite chuffed.”

Finding investment

The engineers had to find a way to continue their R&D after they were told to stop work on the dialysis project, which became the driver for Quanta to be spun-out of IMI. The engineering advances coming out of IMI Vision were disruptive. “It was almost too adventurous for IMI plc to take on. We just made such fundamental differences. You’d need a new type of factory to make the parts and that became a huge capital investment.”

IMI concluded that it couldn’t sustain what was in effect an internal ‘skunk works’, where engineers pursued problems chosen to be the most disruptive. By this time, the dialysis system had quietly reached a stage where the team decided to make IMI an offer, asking Martin Lamb, the CEO of IMI Plc, if it could buy the patents. “Out of naivety you say all sorts of things,” Clive adds, but the offer was serious enough to interest Lamb. The company even offered to put up 80% of the money for a new dialysis business, to back the seven founders. Inevitably called ‘the magnificent seven’, the team then raised enough money, with second mortgages and the like, to acquire the patents. “There was a ceremonial signing of the papers, and the patents were handed over for a pound.”

Medtech meets cybersecurity and big data

The Quantas team had to address cybersecurity challenges before licensing its dialysis system

Developing a new approach to kidney dialysis is hard enough without having to tackle cybersecurity and software reliability in the process. But the team at Quanta had to tackle these challenges before the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) would even think about licensing its systems. At the same time, there was growing scrutiny of medtech safety in general, after patients experienced problems with, for example, breast implants, stents, and hip joints.

With the rise of the Internet of Things and big data, the software issue was important enough for Quanta to step back and reassess what it was going to launch. “We had to go back to round one with FDA guidance and redo the software for the cybersecurity,” Professor Buckberry explains.

Fortunately, Quanta could draw on local expertise in the UK. The engineers took a fresh look at their software after a Royal Academy of Engineering forum on the safety and efficacy of medical devices and systems. Quanta also called upon Dr Philip Bennett FREng who had pioneered the development of technical standards around software. “He recognised that software was safety critical, and it could cause harm in its own right.” Dr Bennett was also on kidney dialysis. “He gave us some great guidance and mentoring to help us get our software back in shape.”

Quanta was also keen to prepare for the rise of big data and artificial intelligence in medtech. “By 2015, you really were beginning to see the tsunami of what you could do with big data.” It anticipated that dialysis machines could become the core around which people would use other medical devices. “There are eventually going to be many personal medical devices and implants that can gather personal data. But that data must be handled responsibly and safely.”

Data security wasn’t something that you could bolt on to a dialysis machine, so Quanta set out to make it an integral part of the system. In this way, Professor Buckberry believes that the MacRobert Award-winning technology isn’t just ahead of the competition medically, it also leads on the software front.

With more than 40 sensors, each machine can monitor the progress of a dialysis session. For example, Professor Buckberry can demonstrate the system and remotely log into company’s portal to see a network of machines and active treatment sessions. He can see that the machines are operating as required, and all the patient data is anonymised.

The dialysis machines have their own health-checking system that Quanta can watch, in the same way that engineers can constantly monitor jet engines in the air. “We can start to look at the health of the machine. Do we do a service call on that machine? Does it need to come back to base?”

Artificial intelligence on a machine and big data could provide even more benefits for patients in the future. “I think medical devices are a unique opportunity. There are going to be so many personal medical devices or implants that give personal data that then work with your machine. This sort of thing is going to rapidly change healthcare,” Professor Buckberry adds.

That was in 2008. “We had a year to make a prototype and to get the funding from venture capitalists (VCs). Then the problem was, how do we find VCs? The engineering was the easy bit.” Clive relates a complicated saga of chance acquaintances, neighbours, and friends of friends who happened to know some VCs. “We were suddenly on the VC merry-go-round across Europe, pitching for money. The first few times you do it, your ‘elevator pitch’ is all over the place. We’re engineers, not salesmen.” The team was asking for £12 million. “It’s not exactly an easy pitch, is it?”

It didn’t help that when they were trying to raise money for a medical technology (medtech) startup in 2008, there was a financial crash. They made it, with what Clive believes was the biggest deal in Europe for medical devices, at the time. After another five years of engineering work, Quanta began to seek medical certification for its dialysis system. The team also had to go back to the drawing board when the wider medtech community realised that it had to navigate the emergence of the Internet of Things (IoT), big data, and related concerns about data security.

Clive paints a picture of a business that, after about a decade of steady progress, ran the risk of stumbling into the so-called financial ‘valley of death’, a period that faces many tech startups, where the original backers, usually smaller investors, are starting to run out of money. “We’re not making any credible returns at that point in time. We can’t scale up manufacturing because we haven’t got the money. And we can’t really switch from prototype parts to volume manufacturing. It was just a whole vicious loop, when you don’t have enough money to scale up, but you need to scale up to make the money.”

Thankfully a chance conversation on the side of a rugby pitch in Queensland, Australia, brought in another investor. “He was quite savvy. He just saw the opportunity. He liked the story. He said, ‘Okay, I’ll fund you’.”

Once again, the money came from outside the UK. “None of our VC funding has come from the UK,” adds Clive. “Our initial investors were VCs in Munich, Dublin, and the National Bank of Greece.”

The fresh backing took the business through the valley of death. More recently, with US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) clearance in December 2020, Quanta reached a stage where it could adopt a more conventional funding model. “Investors were just knocking on the door. You could not turn them away fast enough,” says Clive. In June 2021, Quanta raised $245 million to fund the next stage of its growth. In the past 18 months it has gone from about 110 people to 270.

Career timeline and distinctions

Studied mechanical engineering, Trent Polytechnic, 1979–1983. Master’s in engineering design, 1984. Team Leader, Applied Optics Laboratory, 1984–1995. PhD in TV holography, 1994. Team Leader, Vehicle Physics, BMW, 1995–2000. Engineering Manager, Melles Griot, 2000–2003. Honorary Professor, Heriot-Watt University, 2001. Director of Science and Technology, IMI Vision, 2003–2008. Chief Engineer and Technology Officer, Quanta Dialysis Technologies, 2008–present day. Elected Fellow of the Royal Academy of Engineering, 2011.

As Quanta’s Chief Engineer and Technology Officer, Professor Buckberry sees his strength as an ability to take “more of a helicopter view of the technology”. He has stepped in as engineering manager from time to time, but he always likes to look at the bigger picture. “I get to see all the challenges in the business. I get all see all the new opportunities. It’s great to be able to have that freedom to play again.”

Contributors

Michael Kenward OBE

Author

Keep up-to-date with Ingenia for free

SubscribeRelated content

Health & medical

Kidney dialysis

Small haemodialysis machines have been developed that will allow more people to treat themselves at home. The SC+ system that has been developed is lighter, smaller and easier to use than existing machines.

Engineering polymath wins major award

The 2015 Queen Elizabeth Prize for Engineering has been awarded to the ground-breaking chemical engineer Dr Robert Langer FREng for his revolutionary advances and leadership in engineering at the interface between chemistry and medicine.

Blast mitigation and injury treatment

The Royal British Legion Centre for Blast Injury Studies is a world-renowned research facility based at Imperial College London. Its director, Professor Anthony Bull FREng, explains how a multidisciplinary team is helping protect, treat and rehabilitate people who are exposed to explosive forces.

Targeting cancers with magnetism

Cambridge-based Endomag has helped treat more than 6,000 breast cancer patients across 20 countries. The MacRobert finalist uses magnetic fields to power diagnostic and therapeutic devices. Find about the challenges that surround the development and acceptance of medical innovations.

Other content from Ingenia

Quick read

- Environment & sustainability

- Opinion

A young engineer’s perspective on the good, the bad and the ugly of COP27

- Environment & sustainability

- Issue 95

How do we pay for net zero technologies?

Quick read

- Transport

- Mechanical

- How I got here

Electrifying trains and STEMAZING outreach

- Civil & structural

- Environment & sustainability

- Issue 95