From junk to spectacle

As the clock strikes midnight on each night of the Glastonbury music festival, those who make it to the Arcadia stage are treated to a spectacular show. In front of their eyes, a 15-metre-high, 50 tonne, mechanical, fire-breathing ‘alien’ spider hosts a DJ in its thorax, shooting out lasers and sparks while smaller metal spiders crawl overhead. In the middle of the dark field, flame-throwers, cannons and lasers operate in time with ground-shaking music, while sporadic blasts of heat produce shockwaves so powerful that they almost knock you over.

a 15-metre-high, 50 tonne, mechanical, fire-breathing ‘alien’ spider hosts a DJ in its thorax, shooting out lasers and sparks while smaller metal spiders crawl overhead

The Spider is not just an impressive spectacle; it is a unique example of engineering that is built almost completely from recycled material. The pair behind the creation, Pip Rush and Bertie Cole, have toured the world, impressing crowds with their machine ever since they created it in 2010. The Spider has been evolving with them; at each step along the way, the stage is shaped by the materials the pair can find locally in scrapyards.

The life of the spider

A form of the Arcadia stage now so familiar to Glastonbury-goers first appeared at the festival in 2007. The company responsible for the stage, Arcadia Spectacular, began as a small group of engineers based in Bristol. Rush and Cole got their big break from Glastonbury’s founder Michael Eavis CBE, who invited the company to set up a stage on his land.

Cole, the head engineer on the project, has worked in engineering since leaving school, when he went straight into a position working with tensile structures (a construction of elements carrying only tension and no compression or bending). Rush’s background is in design: he had worked for years in his brother’s Mutoid Waste Company, which specialised in designing structures out of materials found in scrapyards.

Rush and Cole combined their love for engineering and design with their enthusiasm for partying and dancing. Their original idea was for a 360-degree show that thousands could experience, with performers and animatronics moving over people’s heads. Working with re-purposed materials generated unexpected challenges, some of which helped shape an evolving creative vision. Being unable to design a stage without first finding the materials to create it meant that the team had to work around the very specific shapes they managed to find in junkyards.

Rush and Cole combined their love for engineering and design with their enthusiasm for partying and dancing

The first stage they designed was called the Afterburner, which was made in a cowshed in Dorset. Built from metal the pair could find in scrapyards around England, it looked like a combination of a rocket and a post-apocalyptic church with parts of aeroplane sticking out of it. The stage proved popular when it first appeared at Glastonbury; its sound systems were hooked up to a variety of DJs, and Arcadia was born.

Junkyards

Arcadia has returned to every Glastonbury since. The familiar Spider stage debuted in 2010 after three scanning units from HM Customs and Excise security trucks were attached as legs to the original Afterburner stage. In 2012, spy plane engines were added to give it eyes. Cole explains that by reaching out into the audience, the legs provided a sense of immersion, while the eyes gave the stage character. Since then, lighting and special effects, including nine flame cannons and six lasers, have been used to further enhance the experience.

The Spider consists of a central body that includes the DJ booth and upper legs, which are made from helicopter tails. The three large lower legs are fixed to the body with a pivoting joint, designed so that the structure can easily be put together and taken apart. Once the three legs are connected, the team attaches a crane to each one with a pair of chains, which lifts the entire structure up evenly and allows the legs to pivot as it rises.

After the legs are attached to the Spider’s main body, a crane lifts them up so that they pivot and stabilise the structure (left). Ancillary components are attached using hydraulic platforms (right) © Giles Mayall

Because different ground surfaces provide varying levels of friction, the team does sometimes have to assist, using telescopic handlers to draw in the legs as the main body of the structure goes up. Once they are just above the design height, the three legs are connected with 20,000 kilograms of rated steel cables. As the tension is slowly let off the crane, the three legs push back against the cables. At this stage, the main structure is complete and the ancillary components are attached with the use of the crane, telescopic handlers or hydraulic platforms.

As the Spider is made mainly from materials found in scrapyards – at the 2017 festival over 90% of it was constructed from recycled material – putting the stage together not only requires engineering but also huge-scale improvisation.

As the Spider is made mainly from materials found in scrapyards – at the 2017 festival over 90% of it was constructed from recycled material

When the team first developed the Spider, finding the three large ‘crane’ type components from the scanning machines immediately opened up the possibility of using them as legs and the other parts were designed around them. The legs were built to a far higher specification than was originally required. However, rather than downgrading them, all of the other components were manufactured to a matching size, allowing the structure’s payload to carry 10 tonnes more than its design required.

A lot of the materials that were used to build the stage are ex-military. In its current form, the control booth in the Spider’s abdomen is made of the turbine rotors from a TriStar jet engine. Cole and Rush trawl scrapyards to find the parts that they need and often find something unexpected that sparks an idea and takes their design in a completely new direction. The parts are often modelled using computer-aided software. This allows Cole and Rush to move the shapes around and see what is possible virtually, without having to transport huge machinery around.

Safe yet spectacular

🔥 How the team ensures a safe and seamless show

Safety is one of Arcadia’s biggest challenges; while the show looks seamless to the audience, in the background there are rigging changes, people climbing over the stage, pyrotechnics, mechatronics and eruptions of 20-metre flames to consider. Once the parts to build the stage are found, the Arcadia team assesses the materials’ strength so that the stage, and the performers within and around it, can operate as safely as possible.

Throughout the Spider’s design, Cole and Rush sought help from structural engineers, analysing the steel the legs would be built from and using it as the basis to create the stable foundation upon which to build the rest of the structure. The Spider was constructed by a team of qualified welders and engineers in accordance with strict instructions from the structural advisors. Each time it is built, multiple commissioning and then pre-show checks are carried out and signed off before the performance begins and the public can go underneath. The team deploys multiple fail-safe protocols while the show is in progress, to ensure that performances flow smoothly and safely.

Unsurprisingly, there were no existing health and safety protocols for some aspects of the stage. The team works with regulators on the safety mechanisms built into the prototype and they together develop new protocols on a case-by-case basis.

Immersive show

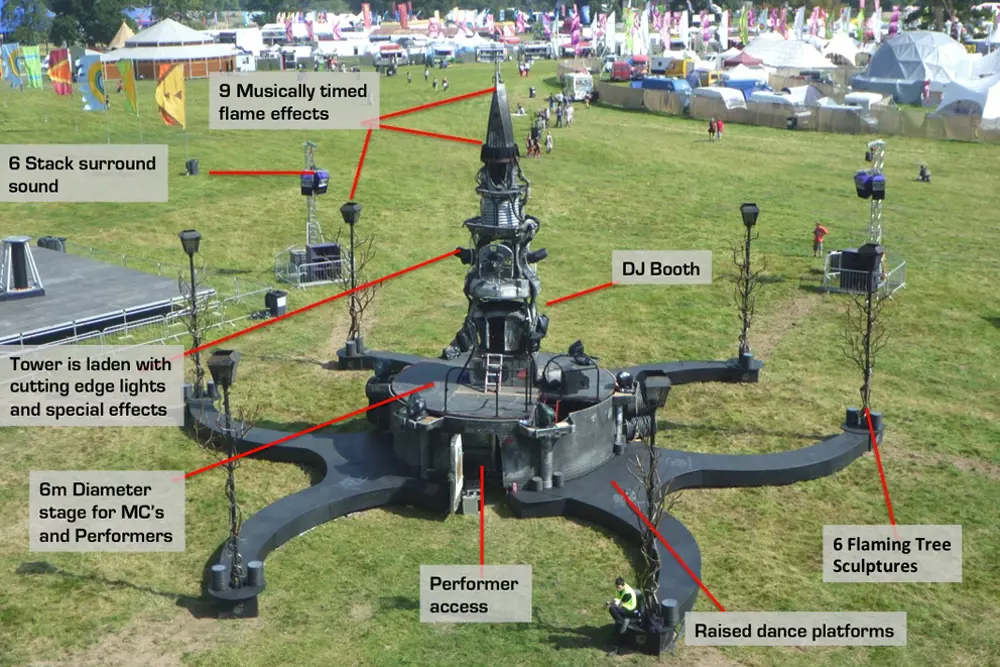

The Afterburner was designed to entertain about 3,000 people and looks the same from all angles. Unlike a traditional stage, it has a front and a back and a transparent 360-degree DJ booth so that everyone in the crowd can see the DJ. A central flaming spire extends from its centre and dancers stand around it on rings, performing simultaneously, while the crowd can dance on its ‘tentacles’ and trees made from old exhaust pipes blow out smoke.

The Spider stage has grown to host 50,000 people, each experiencing the same show whatever angle they watch it from

The Afterburner stage has a number of features

The Spider stage has grown to host 50,000 people, each experiencing the same show whatever angle they watch it from and whether they are at the front or back of the crowd.

The Spider’s performers are suspended from three hydraulic manipulator arms on the top of the structure. They are hoisted up and down, hang freely, and spin at high speed from the ‘claws’, made from log grabbers, at the end of the arms. Each of the three manipulator arms is controlled by an operator who is positioned at the ‘shoulder’ point of each set of limbs. They control every arm movement in sync with the show’s choreography. There is also a team of riggers on the structure who execute a bespoke series of sequences to coordinate human performers with the machine. Meanwhile, three smaller, lightweight spiders, each the size of a car and carrying two people, crawl above the crowd on zip wires with a realistically modelled mechanical simulation of spider movement.

Other stages

Arcadia has designed another stage called the Bug, a six-wheeled, amphibious stage built from a 1960s military vehicle, which is able to entertain up to 3,000 people, rolling on a self-contained structure. Two moulds from a nuclear submarine sonar cone are used at the back to form its wings, which open up to reveal a DJ, sound system and lights inside. The Bug featured in the closing ceremony for the London Paralympics in 2012.

Cole and Rush also have another company called the Lords of Lightning, which specialises in tesla coil shows. One involves two different tesla coils alternating between positive and negative charge, making lightning jump between the two. At Glastonbury’s Arcadia show, two men stood on the tesla coils wearing chainmail suits and duelled with four million volts of electricity between them.

The show uses single tesla coils that are musically modulated, meaning that the frequency of the electrical signal can be used to play a certain piece of music, using the lightning as an instrument.

Around the world

The Afterburner tours the world putting on shows for about 4,000 people each time, and in the past year, the Spider has performed in the US, Australia, Taiwan, South Korea and Croatia. From the start of the design process, the team always aimed to take the stage overseas, so ensured that all of the individual parts could fit into a shipping container – everything needed to set up the stage and for the performance can fit into five shipping containers. On the ground, generic machinery, such as cranes and forklifts, is all that is needed to assemble and disassemble the Spider and speakers.

A slightly simpler show called Landing is performed in other countries, which requires about 50 people and takes around four days to set up. The Metamorphosis show at Glastonbury takes about five or six days and preparation includes the time required for performers to practise, and soundchecks with DJs to get the music, flames, and lasers working perfectly in sync. All of the elements have their own operating systems and are synced to the music using timecode controls.

The large mechanical spider never fails to baffle all those who see it, from passing pedestrians to experienced engineers, and Cole says that explaining it to customs officials and health and safety officers has been an interesting process

The large mechanical spider never fails to baffle all those who see it, from passing pedestrians to experienced engineers, and Cole says that explaining it to customs officials and health and safety officers has been an interesting process. When its flame throwers were tested ahead of a performance in Thailand, intrigued locals who had gone to see what was happening dropped to the floor and took cover.

With Glastonbury taking a fallow year in 2018, Arcadia has announced its own major event in the UK and the team is already developing new ideas and prototypes. Whatever comes next, from the Spider or the Arcadia team, it is certain that it will continue to intrigue and fascinate audiences in the UK and beyond.

***

This article has been adapted from "From junk to spectacle", which originally appeared in the print edition of Ingenia 72 (September 2017)

Contributors

Abigail Beall

Author

Bertie Cole is the Technical Director at Arcadia Spectacular. He had several years’ experience making some of the world’s largest tensile structures before co-founding Arcadia.

Pip Rush is the Creative Director at Arcadia Spectacular. He worked as a sculptor, creating installations and metallic landscapes from recycled materials before co-founding Arcadia.

Keep up-to-date with Ingenia for free

SubscribeRelated content

Arts & culture

How to maximise loudspeaker quality

Ingenia asked Dr Jack Oclee-Brown, Head of Acoustics at KEF Audio, to outline the considerations that audio engineers need to make when developing high-quality speakers.

Engineering personality into robots

Robots that have personalities and interact with humans have long been the preserve of sci-fi films, although usually portrayed by actors in costumes or CGI. However, as the field of robotics develops, these robots are becoming real. Find out about the scene-stealing, real-life Star Wars droids.

Design-led innovation and sustainability

The Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center, the new home of the Greek National Opera and the Greek National Library, boasts an innovative, slender canopy that is the largest and most highly engineered ferrocement structure in the world.

The technology behind ‘The Tempest'

William Shakespeare’s The Tempest is a fantastical play that features illusion and otherworldly beings. Discover how cutting-edge technology, such as motion capture and sensors, has brought the magic and spectacle to life on stage.

Other content from Ingenia

Quick read

- Environment & sustainability

- Opinion

A young engineer’s perspective on the good, the bad and the ugly of COP27

- Environment & sustainability

- Issue 95

How do we pay for net zero technologies?

Quick read

- Transport

- Mechanical

- How I got here

Electrifying trains and STEMAZING outreach

- Civil & structural

- Environment & sustainability

- Issue 95