Making it rain on stage

When theatre designer Simon Higlett was asked to create the set for Chichester Theatre’s 2011 production of Singin’ in the Rain he was enthusiastic but wary: inundating a stage with water can cause problems, from ensuring equipment stays dry and avoiding technical problems to making sure performers are comfortable and actually getting the water on stage. Technical issues had previously meant that a river built at the National Theatre’s Lyttelton stage for Alan Aykbourn’s play Way Upstream burst its banks and flooded the theatre, causing performances to be cancelled. The Times reviewed it with the headline ‘Up River without a Paddle’.

Simon’s main concern was how to deal with the presence of water on stage. A reservoir system for the big rain numbers would have to be in place throughout the show, unlike some previous productions that had moved in huge tanks at the key moments. It would also require a floor solid enough for tap dance numbers and non-slip enough for the rain downpours.

The solutions for making this work for a worldwide tour would rely on a combination of technology, timing and garden furniture.

Turning ideas into reality

Another of Simon’s concerns was creating a believable period setting. Of course, it would be essential for the production to have a spectacular arena for the lead character, Don Lockwood’s, joyful rain dance, immortalised by Gene Kelly in the MGM movie. One problem was all of the changes of scene in the original movie. Simon decided to recreate the back lot of a 1920s Hollywood studio – a filming area for external scenes – which would be the setting for the entire performance, so that no extra scenery had to be brought in from the wings. For the famous dance, the character would be seen to switch on a giant rain-effect system within the studio rather than perform out in a street.

Simon knew that he wanted deep puddles for the dance number. He wanted to recreate the playfulness of Gene Kelly’s film performance when the star not only splashes but jumps into puddles of water. However, it would not be possible to project enough water down from rain bars in the short period of time needed to create these puddles for a five-minute dance sequence onstage; there simply would not be enough time. The whole stage area needed to flood, with a supplemental supply of water to create the illusion of puddling.

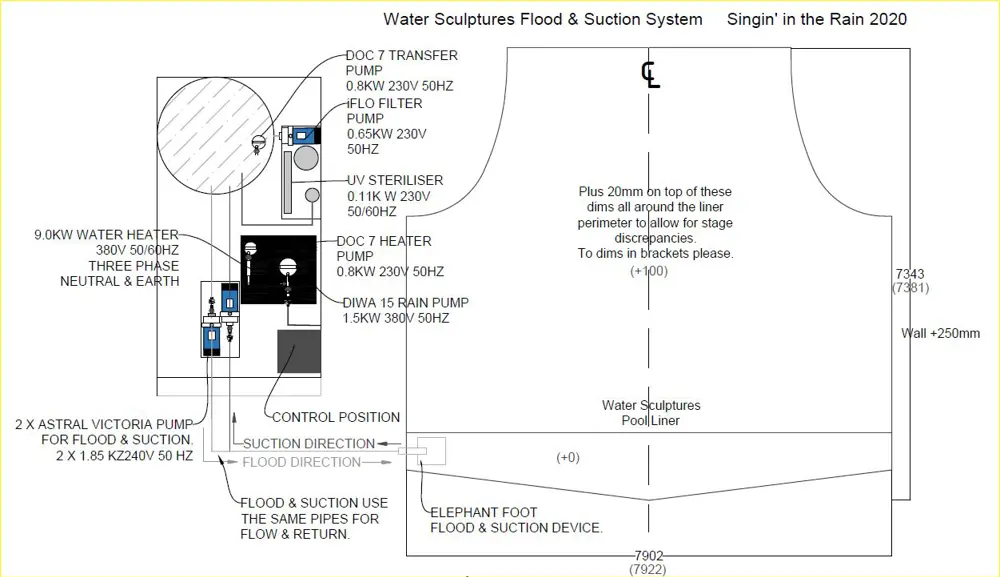

Plan view of the onstage flood and suction system, integrated water storage system and heated rain container, looking from the front of the stage. The system is located in the wings, approximately 15 metres away from the performance area. © Water Sculptures Ltd

The ‘eureka’ creative moments for this project came in gardens. The first was in Simon’s own garden: he was toying with a slatted garden table lying upside down on a waterlogged lawn and when he pushed it downwards, he noticed that the water came up over the slats. This gave him the idea of the water coming up from below rather than from above.

Then, at a friend’s barbeque, he noticed some composite decking boards with narrow-spaced grooves. The hosts told him that these were made of recycled hardwood fibres with a recycled polythene bonding agent that had great anti-slip properties, especially when wet. The grey colour of the hard-pliant boards also fitted in with the black and white décor he had chosen for his silent movie film set. Now, all he needed to do was find someone who could turn his vision into reality. He turned to Morecambe-based Water Sculptures Ltd, which creates both indoor and outdoor spectacular water effects for events such as Olympic and Commonwealth Games displays, business inaugurations, and theatrical performances.

The pool area is lined with a one-millimetre-thick PVC-coated fabric, lacquered with high mechanical strength. Then a three-millimetre-thick Correx floor protection is laid on top. This is fluted and helps drain the water as it is removed. Finally, a stainless steel frame that supports the decking is placed on top © Water Sculptures Ltd

Challenging water effects to create deep puddles on stage

Simon had made things easier for Technical Director William Elliot by positioning the eponymous dance sequence just before the interval. This allows the technical team to deal with the excess water while the curtains are drawn. To get extra value out of the rain-making budget, the director and Simon had added a closing dance number whereby all the dancers dress as Lockwood and perform a final dance that also uses the rain effects.

William saw three main challenges. The first was that the touring element meant that the system needed to fit the stages and set up times of every venue on the world tour, so phone calls determined the space and expertise available at each theatre.

The second challenge was to solve the problem of how to get massive amounts of water onto and then off the stage area while creating a believable rainstorm.

The decking board area that has the pool reservoir underneath measures 7.9 metres across, 7.3 metres long and has a 15-centimetre aluminium wall rim all around to hold in the water. Of the 10,000 litres stored, the pool area needs the amount of water equivalent to roughly 13 bathtubs to overfill it and provide two centimetres of puddle depth above the decking. A further six bathtubs of water is required to supply the rain heads for each rain and dance sequence.

William thought that the flat stage would mean that gravity would neither deliver the water fast enough to fill the pool nor empty it in time. So, his team devised a flood-and-suction system with 1½ kilowatt pumps that delivers the water at a fast and controlled rate through a pair of five-centimetre delivery and suction hoses situated either side of the stage. From the show’s beginning, there is a preset level of five centimetres of water sitting within the reservoir area below the decking, then a combination of pumps and rain from above floods the stage in one minute. While the engineering springs to life beneath his feet, the Lockwood character gently strolls the stage, setting the scene before launching into four minutes of a dancing and splashing tour de force.

The ‘elephant’s foot’ has a greater surface area than that of the pipe connected to it. The shallow inlet allows the water to be sucked out to an extremely low level without the cavitation effect and without the intervention of a traditional submersible pump © Water Sculptures Ltd

Elephant's foot to quickly and quietly remove water

The major issue in William’s second challenge was how to remove the water from the stage quickly and quietly before it overfilled. Because the pool area was shallow, cavitation would occur when drained with a pump and make loud gurgling noises – when cavitation takes place, air bubbles are created at low pressure and as a liquid passes from suction side to release side, the bubbles implode and create a shockwave.

The Water Sculptures team could see that this would be a problem: it would be both noisy and inefficient. The team came up with a low suction device, which then developed into a 45-centimetre-square plate with a five-centimetre outlet on it that sits at the bottom of the pool at the front of the stage. This was dubbed the ‘elephant’s foot’: essentially a box with a shallow inlet.

The elephant’s foot allows the water to be drained out of the pool to a very low level without losing the prime of the pump. The reservoir empties much more quickly and with less chance of it noisily cavitating. During the Lockwood dance it prevents the reservoir from overflowing; then when the rain stops and it is time for the interval, the water level is drained more slowly to the pre-fill level of five centimetres in preparation for the reprise at the end of the show.

Water Sculptures has fine-tuned this innovation and for performances of Madam Butterfly at the Royal Albert Hall, which required a shallow water system, the team drained 55,000 litres in just 12 minutes – a greater water volume than previously.

Rain heads and water safety

Water Sculptures has produced rain for musicians Rihanna and Take That, actors James McAvoy and Sir Ian McKellen, and many others over the years. William’s father and company founder, Byll Elliot, discovered that a nozzle tip used for washing the interiors of heavy-duty industrial process tanks, which came with a variety of apertures and pressures, could be adapted to make realistic rain in different theatrical and commercial settings – from a mist or light rain to a heavy downpour or even a deluge.

Water Sculptures has produced rain for musicians Rihanna and Take That, actors James McAvoy and Sir Ian McKellen, and many others over the years

The company still uses the same techniques and employed heavy droplet nozzles for this production. These are hung from the theatre barrels, retain the pressure until the valves are open and, when released, produce the rain effect with each nozzle delivering about 33 litres per minute at 2.5 bar: a 120% increase in water volume on a standard domestic tap, at a similar water pressure. There are 24 nozzles on set that deliver at least 1,000 litres per minute during the rain sequences.

William’s third challenge was how to safely store and heat the water used. Actor health is paramount, and warm, sitting water is a known hazard for bacterial growth, so four nine-kilowatt heaters warm the water to 28°C for performer comfort. The water is stored in two large tanks and a mini-filtration plant acts like a portable swimming pool plant. The water is treated with bromine tablets to kill any bacteria and a 110-watt ultraviolet steriliser has been installed. The whole system aims to maintain a pH level of 7.4, with the water changed every second week. All interior wet surfaces are cleaned with an antibacterial solution when drained.

The character of Don Lockwood in the water that has been engineered to flood the stage © Jonathan Church Productions and Manuel Harlan

Taking the production on the road and touring the world

The Chichester Theatre’s production of Singin’ in the Rain turned out to be its most financially successful musical ever. The production transferred to the West End for two and a half years and then toured Russia, Australia, Japan, South Africa and Brazil. The rebooted version has been booked into Sadler’s Wells Theatre for performances in 2021 and is due to tour Japan and Russia again in the future.

There will be differences between the production that has been touring the world and the one that will be at Sadler’s Wells, as the team is still solving problems as they arise. Simon is aiming to reduce the current number of 15 lorries needed to transport the show for sustainability purposes. One possibility is to reduce the amount of water used by making the reservoir even shallower. Tests will be done to see if it can be reduced to around 10 centimetres, which could halve the amount of water needed.

Whatever tweaks are made, the essential joie de vivre that thrilled original audiences will surely remain. Indeed, although warned they could get wet, many theatregoers expressly ask for front row seats so that they can get soaked and feel part of the onstage action.

***

This article has been adapted from "Making it rain", which originally appeared in the print edition of Ingenia 83 (June 2020).

Contributors

Simon Higlett is a theatre designer. He has created the onstage designs for a number of stage shows and operas across the world. Simon has also received the Manchester Theatre Award for Best Design, two TMA Best Design Awards and the Helen Hayes Best Design Award.

William Elliot is Technical Director at Water Sculptures. He has worked at the company since 1984 and has travelled the world creating water spectacles for high-profile clients including the Royal Jordanian Family, 2012 London Olympics, Radio City New York, and Broadway West End Theatres.

Keep up-to-date with Ingenia for free

SubscribeRelated content

Arts & culture

How to maximise loudspeaker quality

Ingenia asked Dr Jack Oclee-Brown, Head of Acoustics at KEF Audio, to outline the considerations that audio engineers need to make when developing high-quality speakers.

Engineering personality into robots

Robots that have personalities and interact with humans have long been the preserve of sci-fi films, although usually portrayed by actors in costumes or CGI. However, as the field of robotics develops, these robots are becoming real. Find out about the scene-stealing, real-life Star Wars droids.

Design-led innovation and sustainability

The Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center, the new home of the Greek National Opera and the Greek National Library, boasts an innovative, slender canopy that is the largest and most highly engineered ferrocement structure in the world.

The technology behind ‘The Tempest'

William Shakespeare’s The Tempest is a fantastical play that features illusion and otherworldly beings. Discover how cutting-edge technology, such as motion capture and sensors, has brought the magic and spectacle to life on stage.

Other content from Ingenia

Quick read

- Environment & sustainability

- Opinion

A young engineer’s perspective on the good, the bad and the ugly of COP27

- Environment & sustainability

- Issue 95

How do we pay for net zero technologies?

Quick read

- Transport

- Mechanical

- How I got here

Electrifying trains and STEMAZING outreach

- Civil & structural

- Environment & sustainability

- Issue 95