Music for the masses

With its herringbone-patterned wooden floor and lilac-coloured wall panels, it is easy to forget that at Abbey Road Studios you are standing in one of the most famous recording studios in the world. Studio One, at the heart of the studios in London, looks more like school gym hall than a place where music history was created.

The magic of the place is revealed when you close your eyes: the room has a wide, epic, acoustic feel that befits the orchestras that have played there. There is a slightly smaller space next door that boasts a warmer and more intimate sound, which has attracted some of the biggest musical artists in the world. Acts including The Beatles and Pink Floyd made many of their landmark recordings in Studio Two, as have more recent musicians such as Oasis and Adele.

Acts including The Beatles and Pink Floyd made many of their landmark recordings in Studio Two, as have more recent musicians such as Oasis and Adele

The dimensions, wooden flooring and layers of wall panelling all contribute to the distinctive acoustics that emphasise the mid-range frequencies, making the studios perfect for recording pop songs. Many young and aspiring bands dream of being able to capture some of this sonic aura on their own tunes by recording here.

Today, however, the spread of cheap, high-quality software and digital recording equipment is removing the need for artists to book expensive studio time to produce their tracks. Technology is triggering a seismic shift in the music industry as new artists can record their music at home, without the need to rely on labels and large studios. Given this apparent threat to its business, Abbey Road is taking a somewhat curious approach, by helping these DIY musicians. Its engineers have spent the past five years developing software and online services that allow anyone with a home computer to recreate the distinctive Abbey Road sound in their bedroom.

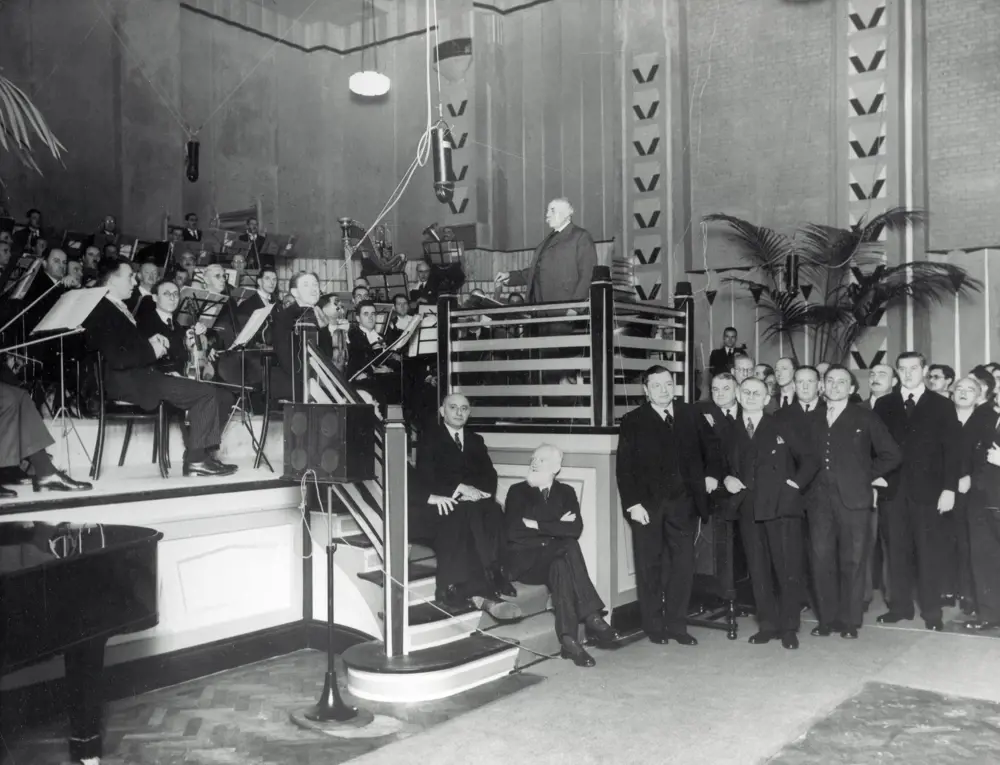

Composer Sir Edward Elgar conducted an orchestra at the opening ceremony of the studios in 1931 on a stage built atone end of Studio One, demonstrating the sound and atmosphere of a live concert that the acoustic engineers hoped to capture © Abbey Road Studios

World firsts

While this may seem an unusual step for an organisation whose business has been built around a special blend of the right venue, equipment and expertise, it is also characteristic of the rule-breaking experimentation that has been prevalent at Abbey Road since it first opened in 1931. Housed within a former nine-bedroom Georgian townhouse in north-west London, it was the world’s first custom-built recording studio.

The studios were the first to use ‘moving coil’ microphones and recorders, which work by producing a small induced voltage in a coil of wire when sound waves hit a diaphragm, after they were introduced by engineer Alan Blumlein in the 1930s. He later developed the world’s first stereophonic recording system at the studios. However, the arrival of The Beatles turned the studios into a household name when the band recorded Abbey Road there and the album cover featured a photo of the band walking across the pedestrian crossing outside. The 1960s and 1970s saw a flurry of experimentation as engineers hand-built tape machines, customised audio compressors and rewired recorders to automatically double-track performances. Tapes were sped up, looped, sliced and slowed down. Amplifiers were even placed inside cupboards to produce distinctive sounds.

It is perhaps fitting that this ageing analogue equipment is now playing a fundamental role in helping Abbey Road break new ground in the digital world

Today, many rare pieces of equipment from this era sit in the corridors between the studios. The building has run out of storage space and the equipment is often still used by artists wanting to get a special vintage sound on their music. The warmth and character that is achieved by using signals through analogue circuits is still highly prized over the harsh ones and zeros of digital. It is perhaps fitting that this ageing analogue equipment is now playing a fundamental role in helping Abbey Road break new ground in the digital world.

Engineer Gus Cook works with BTR-3 tape machines, one of which was rediscovered at the University of Southampton in 2016, in room 11 at Abbey Road Studios around 1965 © Abbey Road Studios

Virtual equipment

Working with Israel-based software company Waves Audio, Abbey Road Studios has been recreating the sound of original Abbey Road equipment as plugins that can be used on audio-editing software. In much the same way as it is possible to use plugins on photo-editing programmes to stylise an image, audio can be similarly tweaked and enhanced.

Using the original schematics and technical drawings stored in Abbey Road’s archive, Waves Audio is able to build virtual circuits that mimic the behaviour of real physical devices, such as resistors, capacitors, diodes, transistors, inductors and valves. Each component is recreated as a software element that behaves just as it would in the real world and the components are then pieced together as they were in the original Abbey Road equipment.

Abbey Road Studios has been recreating the sound of original Abbey Road equipment as plugins that can be used on audio-editing software

Test signals are put through both the original piece of kit at the studio and the virtual circuits so that they can be compared. Engineers then spend days fine tuning the digital version to ensure that it adds the same character and depth to audio signals as the original analogue circuits and valves would have done. At times, staff can find themselves listening to a snippet of drum just half a second long over and over again to see if they can pick up any difference or shift in the digital replica. It is a forensic process.

The list of recording equipment that has already been transformed into digital plugins is a re-creation of music history in itself. It includes 50-year-old tape machines such as the J37, which was specially developed by the studios’ then owners EMI during the 1960s and 1970s, and was used during the recording of The Beatles’ pioneering Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album. There are recreations of Abbey Road’s original reverb plates that were installed into the studios’ echo chambers in 1957 and became popular on the pop albums of the 1960s and 1970s. A selection of mixing desks developed by Abbey Road’s record engineering development department are also available, including the one used to create the psychedelic sounds of Pink Floyd’s The Piper at the Gates of Dawn.

Another plugin allows users to filter their audio through software that recreates the unique frequency response of a rare set of three gold and silver embossed microphones that were custom-made for the Royal family during the 1920s and 1930s. One of them was used by King George VI during Britain’s declaration of war against Germany.

The team at Abbey Road Studios has produced samples of three of theclassical pianos that are kept in Studio One and Two at Abbey Road, includingthe uprights used by the Beatles and a Yamaha CFX1 Concert Grand Piano –an instrument that costs more than £120,000 new © Abbey Road Studios

There are virtual models of vinyl cutting, mastering and playback gear, passive equalizers and artificial double-tracking equipment, an effect that was invented for The Beatles. Each plugin has a graphical interface that replicates the look of the original machine, helping to give a taste of the experience of using it on their computer. It is allowing users to access equipment worth tens of thousands of pounds for less than £100.

Each plugin has a graphical interface that replicates the look of the original machine, helping to give a taste of the experience of using it on their computer

The technique of building the digital replicas component by component also raised the possibility of resurrecting some long gone pieces of recording equipment. While the original physical devices have broken or disappeared, the schematics remain in Abbey Road’s archives, and engineers have been experimenting with creating digital versions from these drawings. Testing how they compare to the real thing could be a good deal trickier.

Fortunately, one piece of good luck may make the job of resurrecting a piece of equipment that has almost legendary status among audiophiles a great deal easier. In early 2017, a student radio station at the University of Southampton rang up to say that they had found an old tape machine that may have belonged to Abbey Road. When they read out the number printed in tiny type on the front, staff at Abbey Road were amazed. It was a BTR-3, a vintage tape machine custom-built by EMI at Abbey Road in the late 1940s, which became the main piece of recording equipment during the 1960s.

There were just three left in Abbey Road itself, but despite their best efforts no-one had been able to get them to work because of bad corrosion and damage in storage. By contrast, the newly discovered machine is in excellent condition, raising hopes that it may be possible to restore it to its former glory.

Unmixing sound

🎸 Isolating the sounds of The Beatles from screaming fans

Digital technology is not just giving old instruments and equipment a new lease of life, it is also resurrecting entire pieces of music. James Clarke, a technician at Abbey Road, tackled the seemingly impossible: unmixing a piece of music after it had been recorded. Throughout the history of recorded music, it has never been possible to successfully unravel the different components of a track if they were recorded together. To overcome this problem, sound engineers record the vocals and all the different instruments in a piece of music on separate channels, mixing them together in the control room.

For albums such as The Beatles’ Live at the Hollywood Bowl, the problem is immediately apparent. On the original recording, the sound of the band is almost completely drowned out by the screaming of 10,000 fans. However, Clarke felt that it was a problem that modern digital technology could help with. He spent five years programming and tweaking software that could unravel all of the separate instruments and vocals from a track. The process involves modelling the music as spectrograms (a visual representation of the spectrum of frequencies) to help identify the component elements.

When he applied it to The Beatles’ album, he was able to isolate each of the four’s instruments and vocals from the messy cacophony, allowing an entirely new remastered version to be created. The new cleaned-up album was released in 2016 to coincide with Ron Howard’s documentary about The Beatles’ live tour Eight Days a Week

Digital instruments

While the recreations of recording equipment at Abbey Road can give some flavour of the distinct sound that can be heard on albums recorded there, it is hard to beat actually playing in the studios. There is an emotional element to interacting with 50-year-old equipment with a weight of musical history behind it that is hard to replicate with software. The unique sound of the studios themselves, and the way sound reverberates between the walls, is also a key part of what artists hope to capture on a record at Abbey Road. To book one of the studios can cost thousands, but for those unable to stretch to that sort of budget, Abbey Road has developed another solution.

It has teamed up with German software company Native Instruments to create digital samples in its studios. Using original drum kits from the 1950s, 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, the studios were set up just as they would have been in each era and the sounds were captured. A musician played each instrument in as many ways as they could possibly imagine: hitting different parts of the snare, tapping rims, using different sticks or brushes, muffling the drum or holding the cymbal. It took three days to sample each drum kit by setting up 30 different vintage microphones from each era around Studios Two and Three. For each instrument, more than 10,000 individual sounds were captured before being chopped up in a process called scripting. These can then be mapped onto a MIDI controller so that the user can play the samples on an electric keyboard or drumpad.

Each of the sampling sessions was organised to mimic the conditions from the era that they were trying to recreate, with drums from the 1980s recorded in the famous mirror-walled drumming room of Studio Two

Using multiple microphones to record the drum samples gives users the opportunity to reblend the balance from each microphone in the software as if they were sat behind the control desk. Each of the sampling sessions was organised to mimic the conditions from the era that they were trying to recreate, with drums from the 1980s recorded in the famous mirror-walled drumming room of Studio Two. The team was also able to source some vintage drum sets dating back to the 1920s from a collector who allowed them to sample the instruments, one of which was insured for more than £1 million, with some of the oldest equipment in the studios.

Abbey road red

🎤 Partnering with innovative start-ups to break new ground in the music industry

The Red audio technology incubator takes its name from Abbey Road’s old research and development wing, the Record Engineering Development Department (REDD), which is where much of the equipment used in the studios’ rich history was built. However, resurrecting such an expensive department was not an option in the modern business world. Instead, Abbey Road decided to look outside its own doors to find those who are pushing boundaries in the music industry and support them instead.

The scheme, which launched in 2015, offers startups a six-month mentoring partnership that gives companies access to Abbey Road’s expertise, facilities and contacts in the music industry. Two new companies are signed biannually in exchange for a 2% stake in equity. For Abbey Road, the benefits extend far beyond any financial return by bringing new ideas and technical knowhow through its doors. The hope is that relationships formed during the incubation periods will lead the studios into new avenues for the business.

This drive to break new ground in the music industry has also seen startups that might be perceived as a potential threat to Abbey Road’s central business being signed up to RED.

Cloudbounce is building music mastering software that uses artificial intelligence (AI) to polish records before they are released. It is something for which Abbey Road has built its own reputation, with a team of experts who master tracks for customers. AI could potentially provide a cheaper alternative to this service and so a rival to Abbey Road’s business, but by working with Cloudbounce, it found that there were actually many ways that the services complement each other. AI could be used to give an initial quick mastering, while humans give the final polish to make it unique.

The other firm in the latest intake is Vochlea Music, a company that is creating a smart microphone that converts vocals into instrumentation. Using machine learning, the software recognises whatever instrument is being imitated vocally, such by humming or beat-boxing, and turns it into the corresponding guitar melody or drum beat for example. The company grew from a graduate project by George Philip Wright, a member of the Royal Academy of Engineering’s Enterprise Hub, at the Royal College of Art and Imperial College London. He is using his Fellowship of the Hub to refine the technology into a product and build a new prototype of the microphone, but he hopes that it may also be adapted into other formats including a high-end live performance tool for musicians.

Previous participants in RED include firms such as Titan Reality, which is developing three-dimensional sensing technology to turn gestures into music. It uses shapes and movements to enable fine control of software-driven instruments. Another called UberChord is developing an app to teach people how to play the guitar.

The future of sound

Despite its history, Abbey Road is not just fixated on the past. It is also looking to the future. It has established an incubator, called Abbey Road Red, to support startups and academics who are developing innovative new products for the music industry.

One company to be supported by Red, California-based OSSIC, triggered interest in what many at Abbey Road hope could be a new direction for the studio. The company is developing headphones that can recreate a three-dimensional audio experience for listeners. Intrigued by the possibilities, Abbey Road has now begun working with researchers at the University of York to find ways of capturing sound in three dimensions. The idea of ambisonics was first developed in the 1970s by British engineer Michael Gerzon but failed to take off because of the expense of the equipment needed to listen to it.

With the development of virtual reality, there is now new impetus to make use of this technology to make the experience even more immersive. Hearing a sound behind or above you could act as an audio guide to help navigate a virtual world.

It has also raised new possibilities for the music world too; with the ability to throw sound at a listener from any direction, it could lead to new creative outlets for artists

It has also raised new possibilities for the music world too; with the ability to throw sound at a listener from any direction, it could lead to new creative outlets for artists. Like many things at Abbey Road, it could help the studio build on its rich past. When the studios first opened, early engineers dreamed of capturing the full live experience for listeners, something that could finally be realised.

***

This article has been adapted from "Music for the masses", which originally appeared in the print edition of Ingenia 72 (September 2017)

Contributors

Richard Gray

Author

Mirek Stiles is Head of Audio Products at Abbey Road Studios. He joined the studios as an assistant recording engineer in 1998 and has worked on projects such as The Lord of the Rings Trilogy

and The Beatles Anthology and with musicians including Muse

and Kanye West.

Jon Eades is the Chief Operating Officer at Figaro.ai and Advisory Board Member to Music Technology UK. He was also the Co-Founder and Chief Operating Officer for The Rattle. At the time of publication, he was Innovation Manager at Abbey Road Studios, heading up Abbey Road Red. He joined the studios in 2011.

Keep up-to-date with Ingenia for free

SubscribeRelated content

Arts & culture

How to maximise loudspeaker quality

Ingenia asked Dr Jack Oclee-Brown, Head of Acoustics at KEF Audio, to outline the considerations that audio engineers need to make when developing high-quality speakers.

Engineering personality into robots

Robots that have personalities and interact with humans have long been the preserve of sci-fi films, although usually portrayed by actors in costumes or CGI. However, as the field of robotics develops, these robots are becoming real. Find out about the scene-stealing, real-life Star Wars droids.

Design-led innovation and sustainability

The Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center, the new home of the Greek National Opera and the Greek National Library, boasts an innovative, slender canopy that is the largest and most highly engineered ferrocement structure in the world.

The technology behind ‘The Tempest'

William Shakespeare’s The Tempest is a fantastical play that features illusion and otherworldly beings. Discover how cutting-edge technology, such as motion capture and sensors, has brought the magic and spectacle to life on stage.

Other content from Ingenia

Quick read

- Environment & sustainability

- Opinion

A young engineer’s perspective on the good, the bad and the ugly of COP27

- Environment & sustainability

- Issue 95

How do we pay for net zero technologies?

Quick read

- Transport

- Mechanical

- How I got here

Electrifying trains and STEMAZING outreach

- Civil & structural

- Environment & sustainability

- Issue 95