A system is needed to deliver on COP26

When COP26 finally took place in Glasgow from 31 October to 12 November, the event had been delayed by a year due to the disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. During that time, the world witnessed a series of devastating extreme weather events linked to climate change. Expectations of the summit were naturally high. It needed to deliver significant commitments to action.

Insights from attending COP26

And did it? My experience having attended the conference makes me more optimistic than some. Regular attendees of COP conferences told me that this year’s summit felt different. The investment and business communities showed up in force and demonstrated their commitment to being part of the solution. If these communities are ready to invest in a net zero future, the challenge now is how we implement solutions at pace and at scale to close the emissions gap, and whether countries across the world have the political will and consistent commitment to collaboration needed to make that happen. We have seen progress: 130 countries have committed to net zero targets; agreements were made concerning deforestation, methane, electric vehicles, and fossil-fuel financing; and coal was mentioned in a climate pact for the first time. Made possible by careful and challenging negotiations, the Glasgow Climate Pact represents an encouraging increase in ambition, and the strongest framework yet for global cooperation.

However, none of this should take away from the fact that the pact alone is not sufficient to stop climate change by 2050. There is so much more to do, and quickly. The sense of commitment across the public and private sector needs to be matched by accountability, monitoring and measurement of outcomes. The real test is whether action is taken at the speed and scale required. By 2030 we’ll know if we’re irretrievably short of the target.

Well before then, the world’s biggest contributors to carbon emissions need to share more detailed plans about exactly how they will radically reduce them. High-income countries should step up their financial support for low- and middle-income countries, many of which will bear the brunt of the worst effects of climate change, even though historically most carbon emissions were from developed countries. If we cannot meet the already overdue commitment of $100 billion a year of financial support for these nations soon, what hope do we have of delivering on the much bigger and more complex challenge of reaching net zero?

Supporting lower-income countries in transitioning to net zero and coping with the effects of climate change is in fact an opportunity to create new markets and opportunities that everyone can benefit from and should be seen as such. This promised financial support should be seen alongside an estimated requirement for $2 to $3 trillion per annum investment to achieve global net zero by 2050, as reported by the Energy Transitions Committee in 2020.

The importance of engineers in tackling climate change

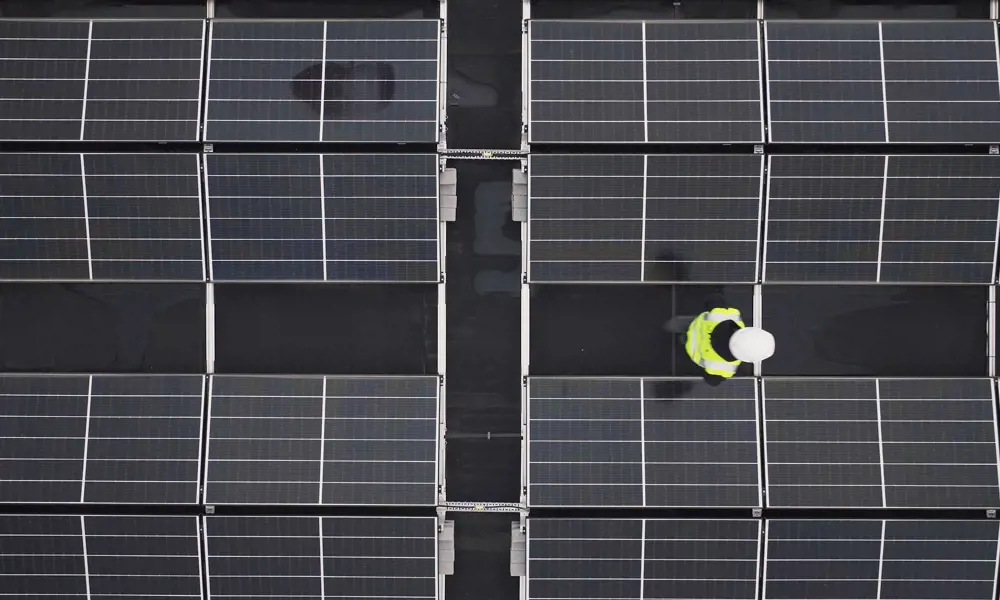

I spent much of my time at COP26 emphasising how important engineers are to tackling climate change. We simply cannot reach zero emissions without engineering. Engineers will design, create and maintain renewable energy technologies and the infrastructure that delivers that energy to our homes, vehicles and workplaces. They will create digital tools that help us adapt our behaviour to reduce our carbon footprint and track our progress in achieving net zero. They will make, improve, and incorporate materials with a lower carbon footprint into our day-to-day lives, and much more besides. Engineers understand how to translate ideas and research findings into real-life solutions, and how to make those solutions work at scale.

The commitments made at COP26 will not be achieved unless engineers help those making net zero policies take a systems approach

The most important point I made at these events was that the way in which engineers think about systems will be vital. Engineers are used to designing practical solutions to complex challenges that have many different dimensions. Because the products of engineering are such an integral part of our day-to-day lives – whether that’s a mobile phone, a plane, our electricity supply, social media networks, or X-ray machines – engineers have to look at the big picture and understand what impact their products and projects will have on the other technologies, people, organisations, and environments they are connected to in order to know that it will work. We call this a systems approach.

All the different ways in which we could reduce carbon emissions will need to work together. So, much like any other products of engineering, we need to think about them as parts of a system and ensure that any one solution doesn’t have an unintended consequence or side effect on something else. The commitments made at COP26 will not be achieved unless engineers help those making net zero policies take a systems approach.

The future path to net zero

This is something the National Engineering Policy Centre is working on. The centre, a partnership of 43 different organisations representing engineers, led by the Royal Academy of Engineering, provides engineering advice to the UK government. Most recently, we have advised on how to identify and make confident decisions – despite uncertainty – about actions that we can take now that will put us on the path to net zero. Actions like helping people to use less energy day to day, making technologies that we already know work – like charging networks for electric vehicles – more widespread, and investing in research and development that can tell us whether new technologies such as hydrogen are viable.

That advice has been received well. It is clear to me that we are being listened to and that the UK government is talking more and more about the need for systems thinking. But it still needs to be put into practice at scale and quickly, while longer term plans are developed. The world is full of great promises, but not as full of great delivery plans. Engineers stand ready to deliver a system that works.

The target of 1.5ºC in global warming is still alive, but only if governments collaborate with engineers to get the job done.

The UK government should be congratulated for hosting such a big summit under exceptional and challenging circumstances. I am naturally very proud of my home city Glasgow for welcoming the world to the conference, and for setting such a good example by committing to reach net zero by 2030. But there is so much more to be done. The target of 1.5ºC in global warming is still alive, but only if governments collaborate with engineers to get the job done.

***

Ingenia has explored other COP conferences, such as 'A young engineer's perspecive on the good, the bad and the ugly of COP27'.

This article has been adapted from "A system is needed to deliver on COP26", which originally appeared in the print edition of Ingenia 89 (December 2021).

Contributors

Professor Sir Jim McDonald FREng FRSE is Principal and Vice Chancellor of the University of Strathclyde. He has been President of the Royal Academy of Engineering since 2019. He was born in Glasgow and studied for his first degree in electrical engineering at the University of Strathclyde, then started his engineering career as a graduate apprentice on the Scottish Electrical Training Scheme. Sir Jim is one of Scotland’s most accomplished engineers, and co-chairs the Scottish Government’s Energy Advisory Board, with the First Minister.

Keep up-to-date with Ingenia for free

SubscribeRelated content

Environment & sustainability

Recycling household waste

The percentage of waste recycled in the UK has risen rapidly over the past 20 years, thanks to breakthroughs in the way waste is processed. Find out about what happens to household waste and recent technological developments in the UK.

Upgrade existing buildings to reduce emissions

Much of the UK’s existing buildings predate modern energy standards. Patrick Bellew of Atelier Ten, a company that pioneered environmental innovations, suggests that a National Infrastructure Project is needed to tackle waste and inefficiency.

An appetite for oil

The Gobbler boat’s compact and lightweight dimensions coupled with complex oil-skimming technology provide a safer and more effective way of containing and cleaning up oil spills, both in harbour and at sea.

Future-proofing the next generation of wind turbine blades

Before deploying new equipment in an offshore environment, testing is vital and can reduce the time and cost of manufacturing longer blades. Replicating the harsh conditions within the confines of a test hall requires access to specialist, purpose-built facilities.

Other content from Ingenia

Quick read

- Environment & sustainability

- Opinion

A young engineer’s perspective on the good, the bad and the ugly of COP27

- Environment & sustainability

- Issue 95

How do we pay for net zero technologies?

Quick read

- Transport

- Mechanical

- How I got here

Electrifying trains and STEMAZING outreach

- Civil & structural

- Environment & sustainability

- Issue 95