Making vital diagnostics more accessible

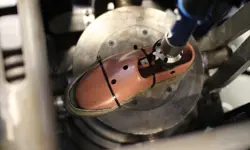

The handheld unit is designed to be suitable for a mobile clinic and includes a built-in display © FlexiGyn / Brett Eloff

Hysteroscopies allow clinicians to see inside the uterus, using a tiny camera on the end of a long, thin tube. However, within South Africa’s overburdened healthcare system, access to the procedure is limited. Patients may wait 6 to 10 months to be diagnosed and treated in hospitals because of the prohibitive cost of mobile hysteroscopy systems. Aside from severe emotional distress, this delayed care can mean that causes of infertility or cancer go undetected.

FlexiGyn’s affordable mobile device aims to solve this problem. It features a slim, flexible scope tip with a patented bending mechanism to navigate the uterus without discomfort to patients.

Bringing hysteroscopies out of the operating theatre

Co-Founder and CTO Edmund Wessels first identified the need for a mobile hysteroscopy device during his biomedical engineering master’s at the University of Cape Town. For the research component of his course, he was paired with a gynaecologist who highlighted the fact that hysteroscopy procedures were largely confined to operating theatres. “In South Africa, the tools to do [mobile hysteroscopies] are incredibly expensive and pretty much out of reach for gynaecologists, in both the public and the private sector,” says Ed.

Convenience aside, early screening is vital. Among the causes of abnormal uterine bleeding are misplaced coils (intrauterine devices) and growths such as fibroids and polyps that can cause infertility. In rare cases, polyps can mutate and become cancerous – but are easily treated when caught early enough. “We can treat these in office in 10 minutes, instead of women having to wait 10 months,” says Chris Meunier, FlexiGyn’s other Co-Founder and CEO. Ed cites research showing that 60% of patients can avoid the operating theatre if abnormalities are caught early via hysteroscopy.

Another issue is the outdated tools often used. “Rigid straight scopes cause a lot of pain to patients, given that it’s not a straight channel that they’re working in,” says Ed. “It needs tools like speculums and tanaculums [gynaecological tools used to aid cervix examination]. So even though it’s a non-invasive procedure, it ends up being invasive to the patient.”

Joint winner of the Africa Prize for Engineering Innovation 2023

👀 Find out the other exciting joint winner

Edmund Wessels is a joint winner of the Africa Prize for Engineering Innovation 2023. His fellow joint winner is electrical engineer, Anatoli Kirigwajjo, who was selected for YUNGA, a community ‘panic button’ inspired by traditional African warning drums. Find out more about YUNGA at yunga-ug.com and in Ingenia’s next issue. Founded by the Royal Academy of Engineering, the prize is Africa’s biggest dedicated to engineering innovation. It awards commercialisation support to African innovators developing scalable engineering solutions to local challenges.

A pain-free procedure

Thanks to FlexiGyn’s patented bending mechanism, the tip of the scope can bend 130 degrees in either direction, for anatomies where the uterus is tipped slightly forward or backwards. “But the most important thing is obviously getting it down to a scale that can enter through the cervix without causing pain,” says Ed.

Doing this involved not only a scaled-down bending mechanism, but also incorporating all the hardware, such as a camera and light source, into a tip less than 4 millimetres wide. A disposable sheath to keep the scope sterile (and therefore reusable) was itself highly engineered. It had to have multiple channels, one for the camera hardware, and another to fill the uterus with saline solution (key to observe the interior cavity).

All of this is incorporated into a handheld unit, making the whole system suitable for a mobile clinic – including controls for navigating, taking videos and images, and a built-in display for the clinician to observe the procedure.

Trials with doctors (who have so far tested the device on anatomical models) have already garnered a lot of positive feedback. Now, the FlexiGyn team is finalising designs based on the user testing, closing a seed round of funding, and preparing for clinical trials. The goal is to have a beta product next year to pilot locally with nurses and gynaecologists before launch.

“We can’t wait to have this in the hospital, in the clinic,” says Ed. He talks of how, while pitching at the Africa Prize finals, women would open up to the team about their experiences and those of friends and sisters who were struggling to get treatment – and how excited they were to see innovation in the space. “It was really cool to get that in this journey – that we’re working on something that people are excited for.”

Keep up-to-date with Ingenia for free

SubscribeRelated content

Health & medical

Kidney dialysis

Small haemodialysis machines have been developed that will allow more people to treat themselves at home. The SC+ system that has been developed is lighter, smaller and easier to use than existing machines.

Engineering polymath wins major award

The 2015 Queen Elizabeth Prize for Engineering has been awarded to the ground-breaking chemical engineer Dr Robert Langer FREng for his revolutionary advances and leadership in engineering at the interface between chemistry and medicine.

Blast mitigation and injury treatment

The Royal British Legion Centre for Blast Injury Studies is a world-renowned research facility based at Imperial College London. Its director, Professor Anthony Bull FREng, explains how a multidisciplinary team is helping protect, treat and rehabilitate people who are exposed to explosive forces.

Targeting cancers with magnetism

Cambridge-based Endomag has helped treat more than 6,000 breast cancer patients across 20 countries. The MacRobert finalist uses magnetic fields to power diagnostic and therapeutic devices. Find about the challenges that surround the development and acceptance of medical innovations.

Other content from Ingenia

Quick read

- Environment & sustainability

- Opinion

A young engineer’s perspective on the good, the bad and the ugly of COP27

- Environment & sustainability

- Issue 95

How do we pay for net zero technologies?

Quick read

- Transport

- Mechanical

- How I got here

Electrifying trains and STEMAZING outreach

- Civil & structural

- Environment & sustainability

- Issue 95